Locating Māori combatants from the Second World War

Māori Battalion, march to victory … However, when entering metadata for Auckland Weekly News subject headings one of the first things to remember is that Māori combatants in the Second World War were not necessarily members of the 28th Māori Battalion. There were Māori soldiers in other battalions or army units, Māori airmen in the Royal New Zealand Air Force and Māori sailors in the Royal New Zealand Navy (although I have only finished from 1939 to 1942 so far and have not come across any Māori sailors in the Roll of Honour yet; and the war is still a work in progress!). Using a few servicemen, here are some examples of the way we can find extra information about Māori combatants from the Auckland War Memorial Museum’s Cenotaph Database and the battalion roll on the 28th Māori Battalion website.

The 1942 Roll of Honour contains three Māori airmen. The first we come across is Sergeant Herbert Samuel (or Bert Sam) Wipiti. Before the war Bert was a junior refrigeration technician in New Plymouth. He won the Distinguished Flying Medal for distinguished courage in aerial combat over Singapore. Sadly, after being promoted to Warrant Officer he was killed when his Spitfire was shot down off coastal France on 3 October 1943. It seems his body was never recovered but he is remembered on the Runnymede Memorial and at Biggin Hill Chapel of Remembrance in England.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Sergeant B.S. Wipiti. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19420422-24-20. |

Blyth Kempton-Werohia was the son of Mr Whetu Henare Kempton-Werohia and Mrs Margery Dinah Kempton-Werohia from Te Puke. After basic flying training in New Zealand, Sergeant Kempton-Werohia was sent to Bombing and Gunnery School in Ontario, Canada. Tragically, he was killed in a training accident and was buried at Beechwood Cemetery in Ontario.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Sergeant B. Kempton-Werohia. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19421028-18-46. |

Flying Officer Kingi Te Aho Aho Gilling Tahiwi was of Ngāti Raukawa descent and came from Ōtaki, near Wellington. Kingi was a Wellington radio announcer before he joined the Royal New Zealand Air Force. After training and being sent overseas, his RAF squadron was sent to the Mediterranean, where he flew during the North African campaign. Flying Officer Kingi Tahiwi was shot down and killed during the Battle of El Alamein and he is commemorated on the Alamein Memorial in the El Alamein War Cemetery.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Flying Officer Kingi Tahiwi. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19421230-23-34. |

Unfortunately the Weekly News Roll of Honour only gives the name, rank and birthplace for each serviceman; his battalion or unit is not recorded. Without any unit information, the chosen way to describe a soldier with a Māori surname or clearly identifiable facial features is to use the subject heading ‘World War, 1939-1945 – Participation, Māori.’ However, one database that does help track down the units that soldiers belonged to is the Auckland War Memorial Museum’s Cenotaph Database. If soldiers can clearly be identified from this as members of the 28th Māori Battalion, we have used the subject heading ‘New Zealand. Army. Battalion, 28’ as part of their description.

While the majority of the Māori servicemen in the 1942 Roll of Honour came from the 28th Māori Battalion, there were a few exceptions. In this case, where battalions or units were known these soldiers were described with the subject headings: New Zealand. Army. Battalion [and then their battalion number].

For instance, Private Frederick George Palmer was the son of Robert and Mare Palmer of Kahutara, Wellington. Before the war he was employed as a linesman on the Mangaonoho Hydro Works near Whanganui. After enlistment, Private Palmer became a member of the 25th (Wellington) Battalion. He was killed on 23 November 1941 during the Battle of Sidi Rezegh.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Private Frederick George Palmer. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19420107-29-20. |

Second Lieutenant Colin Ormsby McGruther was of Tainui and Ngāti Maniapoto descent and came from Pirongia, where he was a farmhand. He was rapidly promoted during training, and on embarkation from New Zealand he was a sergeant in the 18th.(Auckland, Bay of Plenty and Waikato) Battalion. Remaining with the battalion, Colin was promoted to second lieutenant. He was wounded sometime about October 1942, probably during the Battle of El Alamein. When the battalion was converted into the 18th Armoured Regiment in October 1943, Colin became a tank commander. Luckily, he survived the war and the New Zealand Gazette recorded that he was a major when he was placed on the army’s retired list in February 1958.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Second Lieutenant Colin Ormsby McGruther. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19421104-18-5. |

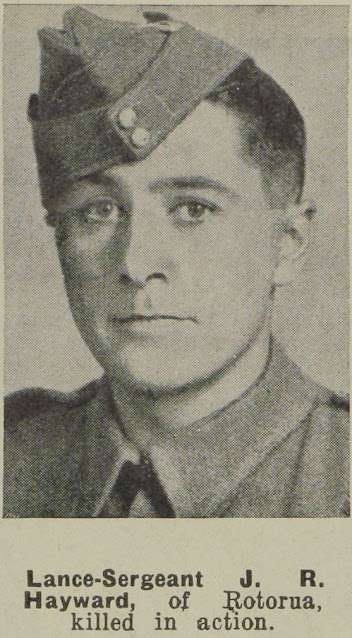

John Russell Hayward was the son of Cecil Hayward and Elizabeth Raureti Mokonniarangi (possibly Raureti Mokonuiarangi) from Rotorua. John identified as Māori. Before the war he worked as a clerk. After training he was posted to 20th (Canterbury) Battalion and had been promoted to Lance Sergeant when he was killed during the Battle of Sidi Rezegh on 27 November 1941. He was buried in the Knightsbridge War cemetery at Acroma, Libya.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Lance Sergeant John Russell Hayward. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19420318-24-2. |

Sergeant Robert Gordon Aro came from Ponsonby, Auckland. He was a fitter and turner before he enlisted. After training he was posted to the New Zealand Army Service Corps because of his skills maintaining vehicles. Sergeant Aro won his Military Medal for saving most of the trucks under his command when they were attacked by enemy tanks on 25 November 1941 during the Battle of Sidi Rezegh.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Sergeant Robert Gordon Aro. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19420401-24-29. |

The other soldiers written about here are clearly identified by the Cenotaph Database as belonging to the 28th Māori Battalion. However please note that soldiers’ names were often spelled incorrectly in the Roll of Honour. It seems that Defence Department officials could not be bothered to check the correct form or spelling of Māori names. When casualty lists were passed to the Weekly News for publication, they were assumed correct and not questioned. Thus mistakes were repeated without checking. In this casual way Private Manu Kuru Te Rore’s name was incorrectly rendered as ‘Private M.K. Terore.’ Private Te Rore came from Kaihu, near Dargaville. Before the war he was a farmer. After training he was posted to the 28th Māori Battalion. Private Te Rore was killed on 23 November 1941 and is remembered on the Alamein Memorial.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Private M.K. Terore (Private Manu Kuru Te Rore). Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19420107-29-9. |

Another soldier to have his name misspelt was Private Natanahira Wiwarena, whose name was rendered as ‘Private N. Waiwarena.’ Natanahira was of Te Arawa descent and came from Whakarewarewa. Prior to enlistment he was a labourer. After training he was posted to the 28th Māori Battalion and served in the Western Desert. Private Wiwarena was killed on 26 August 1942, probably in the closing stages of the First Battle of El Alamein. He was buried in the El Alamein War Cemetery, Egypt.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Private N. Waiwarena (Private Natanahira Wiwarena). Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19421104-18-31. |

Private Rawiri Ngatoro was also known as Dave Ngatoro. However the Weekly News caption for his photograph recorded his name as ‘Private R. Ngatora.’ Rawiri came from Te Araroa and prior to enlistment he was a labourer. After training he was posted to join the 28th Māori Battalion in the Western Desert. The Cenotaph Database does not have much more information about him, but according to the Weekly News Private Ngatoro was accidentally killed in early 1942.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Private R. Ngatora (Private Rawiri Ngatoro). Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19420311-24-31. |

In some Roll of Honour captions, Māori names were omitted altogether. Private Robert Aperahama Oliphant Stewart was recorded as just ‘Private Robert Oliphant Stewart.’ Even the memorial inscription in the Auckland War Memorial Museum’s Hall of Memory simply records him as R.O. Stewart. Robert claimed descent from the Mataatua waka, and he came from Whakatane where he was a printer prior to enlistment. He belonged to the 28th Māori Battalion and was killed on 16 December 1941 during Operation Crusader. He is remembered on the Alamein Memorial.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Private Robert Aperahama Oliphant Stewart. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19420211-25-14. |

An even more glaring error was committed (or transposed) for the unfortunate soldier recorded as Private K.P. Wirlpo; ignorance of the Māori language, or just bad printing? When I searched the Cenotaph Database it could not find such a name, or even someone named K.P. Wiripo. Fortunately the Cenotaph Database search can be customised, so I searched all casualties for his hometown, Herekino. This found Kupu Penewiripo. And interestingly, his parents were listed on the Cenotaph Database as Mr Pene Wiripo and Mrs Ere Pene Wiripo. The 28th Māori Battalion Roll confirmed that he did enlist as Kupu Penewiripo, but also showed he was later recorded in the battalion’s War Diary as Private Kupu Pene Wiripo. Kupu was a labourer prior to enlistment. After training he was posted to the 28th Māori Battalion. Sadly, the War Diary recorded that Private Pene Wiripo accidentally shot himself on 12 November 1942 and a Court of Enquiry concluded that he died by misadventure. The official history of the 28th Māori Battalion recorded that he died on active service. Kupu Pene Wiripo was buried at the Halfaya Sollum Cemetery in Egypt.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Private K.P. Wirlpo (Private Kupu Pene Wiripo). Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19421230-22-47. |

Second Lieutenant Pineāmine Taiapa (Ngāti Porou) is more well-known as a Māori artist and master carver than for his military career. Raised by his uncle, Pineāmine was educated in matauranga Māori and attended Te Aute College. He became a Māori All Black and played during their 1922 tour of Australia before starting to learn to carve, first at home in Tikitiki and then at the newly established School of Māori Arts in Rotorua. By the Second World War he had already worked on many meeting houses across Aotearoa, including the centennial house at Waitangi. As a Māori leader he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 28th Maori Battalion but was wounded on 15 December 1941 in fighting during Operation Crusader. He returned to the battalion and was promoted captain in October 1942. After the war he worked as a rehabilitation officer before returning to his work as a renowned master-carver, playing a major role in Māori cultural rejuvenation.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Second Lieutenant Pineāmine Taiapa. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19420211-24-4. |

Lieutenant Colonel Eruera Te Whiti o Rongomai Love was the first Māori officer to command the 28th Māori Battalion. Lieutenant Colonel Love was also known as Eruera Te Whiti Rongomai, Tiwi or Tui. Eruera was of Te Āti Awa descent and he came from Petone. Before the war he worked as an interpreter. He was also a territorial and was a company commander in the 1st Battalion of the City of Wellington Regiment. He was transferred to Army Headquarters to help form the Māori Battalion. In 1940 he joined the battalion as a captain. He was mentioned in despatches, for capably handling the Māori Battalion as its temporary commander in November and December 1941. Subsequently on 13 May 1942 he became the first Māori officer promoted to command of the battalion. However Lieutenant Colonel Love was killed on 12 July 1942 during the First Battle of El Alamein. He was buried in the El Alamein War Cemetery.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Lieutenant Colonel E. Te W. Love (Lieutenant Colonel Eruera Te Whiti o Rongomai Love). Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19420729-18-2. |

Ake Ake kia kaha e.

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.