Readers and readings: traces of use in the Auckland Libraries First Folio

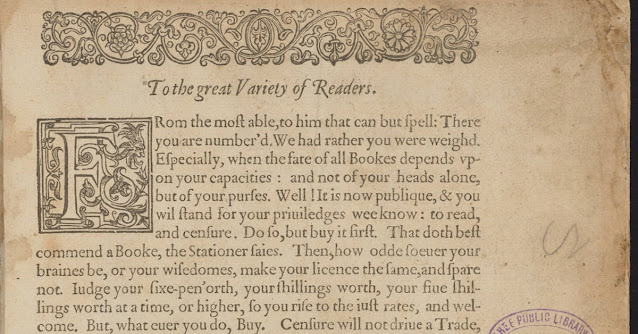

At the start of Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies, otherwise known as the ‘First Folio’, there’s a note from Shakespeare’s former colleagues to the book’s potential consumers. “To the great Variety of Readers”, it begins, before outlining the reasons people might want to buy – and read – this unprecedented collection of plays.

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 15. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

The First Folio was published in 1623; its surviving copies are now four hundred years old. As a consequence, they have indeed encountered a “great Variety of Readers”, and the copy of the First Folio held in the Sir George Grey Special Collections at Auckland Libraries is no exception.

Traces left by this copy’s early owners and readers testify not just to the multiple hands through which the book has passed, but also to the great variety of readings the book has received. Published in a period when many people read with pen in hand, the Auckland First Folio preserves multiple moments when readers responded to the Shakespearean text in ways that were consistent with conventional early modern reading practices. But it also highlights the way that any book from this period – regardless of its future as a highly prized cultural object – could be seen as a repository of blank paper, with margins that stood ready to receive comments and compositions entirely unrelated to the text they framed. This blog post explores some of the marks and marginalia in the Auckland Libraries First Folio in order to demonstrate these points, and to introduce contemporary readers to the unique features of the sole copy of this book held in Aotearoa.

The first trace left by an early modern reader in the Auckland First Folio can be found on one of book’s early pages, which retains the signature of one “Charles Grylls”, accompanied by a date: April 1676.

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 13. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

Grylls was Sherriff of Cornwall, and seems to have engaged with the book several times that year – notes in his hand accompanied by the date “1676” also appear on pages of The Winter’s Tale and 1 Henry IV. As a high-ranking official, he is the type of “gentleman reader” that in the late sixteenth- and early seventeenth centuries was often assumed to be the target audience for early modern printed drama. But Grylls’s name is not the only one in the book: in the top margin of a page of Othello, written twice in a different early hand, is the name “Anne Hearle”.

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 851. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

The scholar Emma Smith has identified Anne as “part of the extended Grylls family”, and the presence of her name supports seventeenth-century publishers’ growing acknowledgement that women readers were also a significant part of the market for printed drama: in 1647, the publisher of the collected dramatic works of two of Shakespeare’s rivals, Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, wrote that “in [printing] works of this Nature” (i.e. plays), “Ladies and Gentlewomen […] must first be remembered” [my italics].1

The names of Charles and Anne are not the only ones in the book. On an early page of the first play in the volume, The Tempest, another early hand writes “William” next to a line delivered by the character of Miranda.

.jpeg) |

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 26. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

In this line, Miranda is responding to a question from her father Prospero, about what – and who – she can remember from her distant childhood. The unexpected positioning of William’s name – nestled in amongst the dramatic text, as though it were a part of it – makes us question whether this name belongs to the reader who wrote it, or whether this is a moment where that reader responded to same prompt as Miranda, and produced the name of a half-remembered figure from his or her childhood, just as Miranda conjures up the memory of the waiting-women who looked after her as a toddler. If this is the case, the inscription of the name is evidence of a common early modern playreading practice, in which readers engaged closely with small parts of the text, rather than the whole.

Evidence of this habit can be seen in further manuscript additions made by early readers of the Auckland First Folio. Although several plays in the volume have inscriptions on their initial pages that seem to indicate that they have been read in their entirety (signalled by the Latin inscription “Iam legi” – “I have already read”), by far the most common type of readerly intervention in the book are the small crosses or dashes that readers made in the margin next to particular lines or passages of text. These types of marginal marks are found throughout surviving copies of books from the early modern period, and reflect the way that readers in this period belonged to a culture of ‘commonplacing’. They had been trained in school to read with an eye to extracting reusable phrases that they could recycle in their own compositions, and many readers carried this habit over into their adult leisure reading.

In the Auckland First Folio, marginal ink marks can be found next to lines in roughly half of the comedies and histories, but only two tragedies. Tragedies were more likely to furbish the type of aphoristic sententiae that were considered apt material for one’s commonplace book, a repository of reusable phrases on universal themes – such as the line picked out in King Lear: “Men must endure/ Their going hence, even as their coming hither”.

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 820. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

One of the reasons there may be so few lines picked out in the tragedies in this volume, however, is that commercial drama had a reputation for being able to provide other sorts of material to readers, for reuse in more pragmatic, real-world contexts. At the end of the sixteenth century, the playwright and satirist John Marston writes a mocking verse, which makes fun of a young man who has nothing original to say, but “writes, […] rails, […] jests, […] courts, what not/ And all from out his huge long scraped stock/ Of well-penn’d playes.”2 The Auckland First Folio supports this image of the playreader who seeks out jests to pass off as his own, or lines to use when courting: the marginal marks that signal potential ‘scrapings’ in this copy are often next to jokes or generic lines of flattery.

So, for instance, in The Comedy of Errors, a vertical score in the margin isolates the call-and-response banter between Antipholus of Syracuse and Dromio of Syracuse in which Dromio describes Nell, the “kitchen wench”, as “spherical, like a globe; I could find out countries in her.” (Antipholus proceeds to ask him where, then, in her body he found particular countries such as Ireland, Scotland, France, eliciting bawdy responses that also poke fun at national characteristics.) This type of standalone question-and-answer-based jest (it has little to do with the play’s plot) clearly appealed to readers: a similar formula underpins the exchange between Orlando and Rosalind in As You Like It in which he gets her to tell him how different figures (lovers, priests, convicts, lawyers) experience the passage of time. In the Auckland First Folio, Rosalind’s responses in this exchange are marked out by ink dashes.

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 221. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

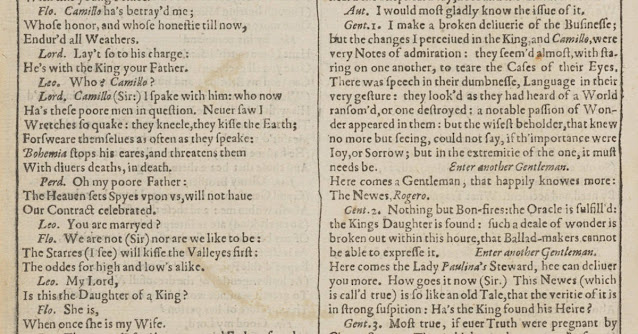

In a different play, The Winter’s Tale, the ink marks are crosses, and they pick out lines that, rather than being humorous, are the types of compliments that Marston envisages lovestruck playreaders seeking out to flatter the object of their affection. One cross accompanies Florizel’s line to Perdita: “For I cannot be mine own, nor any thing to any,/ If I be not thine”; another accompanies a line delivered by the character of Camillo, struck with wonder at the sight of the shepherdess Perdita: “I should leave grazing, were I of your flock,/ And only live by gazing.”

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 315. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

These lines are carefully rhetorically constructed (the juxtaposition of mine/thine; the rhyme of grazing/gazing) and it’s easy to see why they might have appealed to a would-be lover who lacked confidence in his own ability to compose creative compliments.

Other annotations in the volume testify to the confidence early modern readers had when it came to what scholars of the period describe as “perfecting” the book. The complexity of the early modern printing process meant that, invariably, a few typos would make their way into the printed text. Readers who spotted these were quick to correct them with their pen, showing that they understood what the text should have read, and thereby transforming the volume – via their manuscript corrections – into a more “perfect” version of itself. Emma Smith discusses several of the corrections in the Auckland First Folio in her book on copies of the publication: the amendment of “dxile” to “exile” for instance, and of “Mo sir” to “No sir”.3

One particularly interesting example of perfection is the tricky word “unaneled” in the Ghost’s speech in the first act of Hamlet, which was clearly a word that the compositor (the person who arranged the individual letters that made up the page of text) struggled with the spelling of, partly because even in the early modern period it wasn’t a very common word. It refers to a part of the Catholic process of providing last rites for a person on their deathbed.

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 772. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

Its spelling got blurred over the years with that of the similar-sounding word “unannealed”, which is clearly what the reader of the First Folio is thinking of when they add that apparently missing “a”. But even if they’re not sure of the spelling, they know what the word means, and their addition of an adjacent definition (“i.e. unannointed”) makes the word’s meaning more transparent for future readers. This is a different way of “perfecting” the printed text, one that prefigures the later editions of Shakespeare we are used to reading today, which unpack difficult or archaic words to aid comprehension.

Finally, there are a number of annotations made by readers of the Auckland First Folio which seem to bear only a tangential relation to the adjacent Shakespearean text – or at times no relation at all. At the time when it was published, this volume wasn’t just a repository for some plays that would increase exponentially in popularity over the coming centuries – in the margins that surrounded the text of these plays, it was a source of available blank paper in a period when this was a relatively expensive commodity.

As such, the book could become a practical self-improvement tool, for instance when readers used the blank space of the margin to practice their handwriting (or test their pen) by copying out adjacent lines of text. In the Auckland copy of the First Folio, we can see an example of this in the top margin of a page of The Comedy of Errors, where a reader copies out the two key words in the play’s title, “comedy” and “errors” – adding next to them the word “Forgive”, perhaps indicating their view that actions made in error should be forgiven.

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 117. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

On one of the pages of Hamlet, the line in the top margin of the page is instead an adjacent line of dramatic dialogue, Hamlet’s line to Gertrude: “How is it with you Lady?”.

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 785. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

In the bottom margin of a page of the second part of Henry VI, what looks like practice at forming individual letters is in fact something more mysterious – here the reader has turned the volume upside down and used the space beneath the text to write something in what looks like a type of code, perhaps one where each letter represents a longer word.

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 482. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

That this is how the code works can be inferred from the parenthetical phrase in the middle of the second line, where the reader makes a mistake and writes out the word “thanks” in full, before scrubbing out the final five letters and following them with “b t g” – turning this into the recognisable phrase “thanks be to god”.

The fact that the passage of code isn’t even written using the same alignment as the printed text signals that, in instances like this – and others in the Auckland copy – Shakespeare’s text was incidental to the usefulness of the book as a place to inscribe one’s own written compositions. On a page of Coriolanus, for instance, the outer margin offers space for a reader to jot down what seem to be the closing lines of a letter: “from you a Saturday last this convenient time shall only let you know that I am yours to command”.

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 650. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

Meanwhile, the outer margin of The Winter’s Tale provided space for another reader – probably Charles Grylls himself – to transcribe a proverbial ditty: —"the devill was sicke the devill a monck would bee |the deville was well the deville a monck was hee”.

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 326. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

As Emma Smith points out, this couplet is “not immediately relevant” to the adjacent text of the play, and its presence – like that of the previous examples – instead reflects the way that copies of Shakespeare’s First Folio have, over the course of their 400-year old lifespans, been far more to their readers than simply the repositories of much-beloved plays by a famous dramatist.4 A final example of this? The page of The Winter’s Tale that clearly shows the ring of a wineglass stain.

|

| Image: Detail from Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories & tragedies. Isaac Iaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623. Kura image 324. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

Shakespeare’s First Folio might now be a highly prized rare book, whose 400-year publication anniversary is being commemorated across the globe – but as the Auckland Libraries copy demonstrates, in one earlier life, it was a coaster.

Author: Dr Hannah August

Hannah August is Senior Lecturer in English at Massey University, and the author of Playbooks and their Readers in Early Modern England (Routledge, 2022).

References

1. Emma Smith, Shakespeare’s First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), p. 97; Humphrey Moseley, “The Stationer to the Readers”, in Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, Comedies and Tragedies (London, 1647), sig. A4r.

2. John Marston, The scourge of villanie (London, 1598), sig. H4r.

3. Smith, p. 149.

4. Ibid., p. 97.

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.