Among the Auckland Libraries collection of incunabula - early printed books - is a copy of the Golden Legend printed by William Caxton in 1483, which is one of only 33 surviving copies in the world.

|

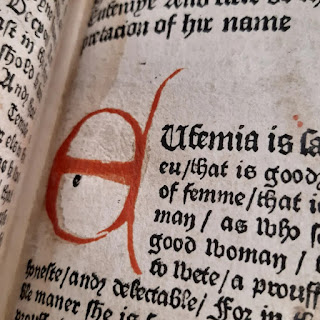

| Detail of the Golden Legend; the printed English is comprehensible to the modern reader. |

William Caxton was born about 1422 and died about 1491. He is thought to be the first person to introduce a printing press into England and the first English retailer of printed books - most significantly, books in the English language, which he translated from earlier medieval and classical texts. After working in Bruges and seeing the recently-invented printing press in action, Caxton returned to England and set up a press in Westminster in 1476. He had translated a collection of stories associated with Homer's Iliad, the Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, and his printed version was in high demand. Realising there was a market for English language texts, he produced an edition of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, and went on to publish chivalric romances, histories, and other classical works.

|

| Caxton's printer's mark, in the Boke of Eneydos, 1490. |

Caxton's publications had an important impact on the English language; even though he wished to provide the closest replication of foreign language texts into English, because he was under such time pressure to publish as much and as quickly as possible, he sometimes simply transferred French words rather than translating them. Due to the popularity and wide influence of his works, this cemented the wholesale transference of French words into the English language.

Auckland Libraries holds three Caxton publications, all donated by Governor George Grey:

The Polychronicon, printed in 1482, a history of the world from the Creation to the present day originally written in Latin by Benedictine monk Ranulf Higden more than a century earlier. There are only 32 surviving copies in institutions around the world according to the

ESTC (English Short Title Catalogue).

|

| The Polychronicon. |

The

Boke of Eneydos is an English translation of Virgil's

Aeneid, printed by Caxton sometime after 1490. There are only 15 surviving copies in institutions around the world reported in the ESTC.

|

| The Boke of Eneydos. |

Legenda aurea sanctorum, sive, Lombardica historia, commonly known as the

Golden Legend was printed by Caxton in 1483, based partly on the original Latin saints' tales compiled by Jacobus de Voraigne in the thirteenth century, partly on the fourteenth-century French translation by Jean de Vignay, and also on an anonymous English translation, the

Gilte Legende, from about 1438.

Hagiography was a popular subject at this time, and Jacobus de Voraigne's text was extremely widely read. Once printing was invented in the 1450s, editions appeared quickly in almost every major European language, as well as in the original Latin. Up to 1501, it was printed in more editions than was the Bible. Caxton's translation was first printed in 1483, and was reprinted multiple times, with a ninth edition published in 1527.

|

| The Golden Legend. |

Each chapter of the Golden Legend concerns a different saint or Christian festival, and they are ordered according to the feast days through the calendar. The book is a valuable source of information on the symbols and attributes of saints, making it a kind of encyclopaedia of medieval saint lore for historians and art historians.

Recently, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections staff had cause to look more closely at our copy of the Golden Legend for an international research enquiry undertaken for Dr Takako Kato of De Montfort University in Leicester, U.K. Here are some of features of interest that distinguish our particular Golden Legend.

|

| Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections staff member with the Golden Legend. |

Our copy is bound in a later, likely Victorian, binding of green morocco (a type of goatskin leather) with gold stamped decoration. It is a large heavy volume at 38cm, and has to be supported on a beanbag when opened, as can be seen in the photo above. Our copy is imperfect; it should have 449 leaves, but is missing all the beginning pages up to leaf 39, and all the last pages after leaf 431, as well as 14 other leaves throughout. The most perfect surviving copy in the world is held by Cambridge University, so we were able to use images of that copy as a reference to confirm which pages are missing from ours.

|

| Binding of the Auckland Libraries copy of the Golden Legend. |

The pages are bound in 'quires' of eight leaves together, each marked with a 'signature' in alphabetical order; in the 'f' quire, for example, the right side of the first page would be marked 'f1r' (r for recto) in the lower right-hand corner. The reverse side of that page is referred to as 'f1v' (v for verso), although only the recto sides are physically marked. As the original medieval pages in the Auckland Libraries copy were re-margined at some point and each set into a border of different paper, often these signatures have been cut off or damaged, making it difficult to tell sometimes which page you are looking at!

There is damage to most pages in the Auckland Libraries copy. Water stains occur throughout different sections, and corners or sometimes whole sides of a page are torn or missing. There is not much in the way of marginalia as the margins of the original pages have been closely cropped. Tears in the pages have mostly been mended with small patches of tissue paper.

|

| Damage to these pages has been patched; the difference between the original medieval paper and the more modern border is clear. |

One unusual repair was discovered during our recent close study, where a vertical tear in the paper had been stitched up with thread - likely an older mend.

|

| Stitched repair to a damaged page. |

One feature which helps bibliographic researchers determine whether the pages are original, or have been bound in the correct order, is the watermarks. These are created during the production of the paper, by attaching a decorative design made of wire to the mesh grid used to set the wet fibrous paper pulp, and were used in European paper production since the twelfth century to indicate the paper mill, or the town and factory, where the paper was made. Study of watermarks allows researchers to date manuscripts and incunabula with surprisingly high accuracy, as well as build knowledge of the technical aspects of paper production, trade and distribution. [

Rückert, et al, 2009.] Watermarks are only visible when the paper is held up to the light. There are several different watermark designs in the Auckland Libraries copy of the Golden Legend, including symbols of a bull, a hand, a ring and star, a quatrefoil, and a lamb, as below:

|

| Watermark in the design of an Agnus Dei, lamb of God. |

There are 70 illustrations spaced throughout the book. These are woodcut prints, usually the width of one column but occasionally bigger, and serve to illustrate the surrounding text. Here is an image of Noah bringing animals onto the Ark.

|

| Illustration of Noah's Ark. |

While all the main text and the illustrations have been printed in this edition of the Golden Legend, there remains one element done by hand: the large initial letters that have been painted in red to mark the beginning of new sections. These red initials, and the small red paragraph markers which are infrequent in our copy, are known as rubrication - a term which comes from the Latin rubrīcāre, 'to colour red.' The word 'rubric' is now commonly used as a generic term for all headings, though originally it referred only to these headers done with red ink.

The variations in style of the rubricated initials helps to indicate whether different scribes worked on the text. A small guide letter is printed in the space to signal to the scribe which letter was needed. Although the initials in this edition of the Golden Legend are not as decorative as those in some other medieval manuscripts and books, they are still stylised and elegantly drawn.

Can you identify these letters? (Answers at the bottom of the page!)

In some later productions the initials are printed, but retain the aesthetic of the hand-painted letters, such as in Caxton's Boke of Eneydos, published in 1490:

|

| Printed initial T in the Boke of Eneydos, 1490. |

Close study of texts such as these allows scholars to build up a more detailed picture of how books were produced, distributed, and used in the past. The Golden Legend is important due to its cultural influence, but also as an example of early printing at the beginning of an age of more widespread literacy, in which more value began to be placed on writing and reading in the English language.

(Initial answers: T, S, M, F, E)

Author: Harriet Rogers

Educational .

ReplyDelete