Elementary, my dear Watson. Not so. Sometimes editorial cartoons can just be humorous or ‘funny-peculiar’ pictures, but very often they have deep, intriguing meanings for readers based on current news of the day. This is usually the case with political cartoons, which use wit, satire and symbolism to convey their clearsighted but ironically subversive messages. Here is a selection of cartoons published by the

Auckland Weekly News during 1920, with some ideas about what they mean.

Our first cartoon is by

Weekly News cartoonist Trevor Lloyd. He entitled it ‘His Majesty the Jockey’ because the Auckland tram strike supporting the jockeys’ work grievances took place on King’s Birthday, 1920. To interpret the cartoon, you should consult Papers Past about the jockeys’ work dispute and the tram strike. The tramwaymen refused to run trams going to the races at Ellerslie. In the cartoon a ‘nanny’ from the Federation of Labour (who might be a caricature of Mr J. R. Roberts, the Transport Workers’ Federation spokesman) pushes a diminutive jockey out to stop a tram running to the races. In the centre another line of trams for the races lies idle. In the background, men and women crowd onto a bus bound for Remuera, because the buses were the only way to get to the Ellerslie Racecourse while the strike was in progress.

Our second cartoon is also by Lloyd. Here Prime Minister William Massey is fishing among the sharks. To interpret this cartoon you need to read the

Weekly News for 17 June 1920 which stated that Massey’s Government had established a tribunal to deal with New Zealand profiteers ‘but that so far only a few “small fish” have been caught.’ Lloyd is implying that the ‘flannel-fish’ and ‘Tommy-cod baby food’ Massey is using to bait his tribunal’s ‘rod of correction’ is not effective enough to catch slippery ‘vaseline cod’, let alone the large profiteer sharks circling the New Zealand economy. The small fish that swallowed the alarm clock is fascinating; perhaps Lloyd thinks Massey is like Peter Pan living in Neverland and waiting for the crocodile!

Our third cartoon by Lloyd is about the voracious financial appetite of the Massey Government. In a drawing based on Oliver Twist, Bill Massey, who was Minister of Finance, goes back to New Zealand taxpayers with his empty bowl and asks for another £24,800,000 loan, hiding behind his back the ‘compulsory levy’ sledgehammer he will use to force taxpayers to pay it. In the background, identifiable members of Massey’s cabinet greedily imagine what they can do with dollops of the money he is about to extort from the long-suffering New Zealand public.

Our fourth cartoon is about the Irish struggle for independence from Britain. The

Punch cartoonist portrays typical English condescension about the ill-educated and uncouth Irishman’s quaint and insane desire for independence. But first, one must teach them to read and spell. So in the cartoon, British Prime Minister (and magician) David Lloyd George tells his audience he has offered a porcine Irish politician a republic as long as he can spell ‘home rule’ from the letters he has placed in front of him.

Britain’s position was that the Irish were not politically ready for responsible self-government. This patronising view was shared in New Zealand where Orangeism and Éire-phobia were alive and well at the time. So our fifth cartoon is by

Weekly News cartoonist Trevor Lloyd. It shows Prime Minister Lloyd George trying to lay down the law in a typically mad Irish homestead, where the pig is kept in the kitchen and Sinn Féiners fight other Irishmen. Even the mother, who embodies Southern Ireland, is about to hurl and smash a shamrock-decorated plate, symbolizing the independent republic the Irish are fighting for. Meanwhile, outside the door leprechauns brawl with their shillelaghs.

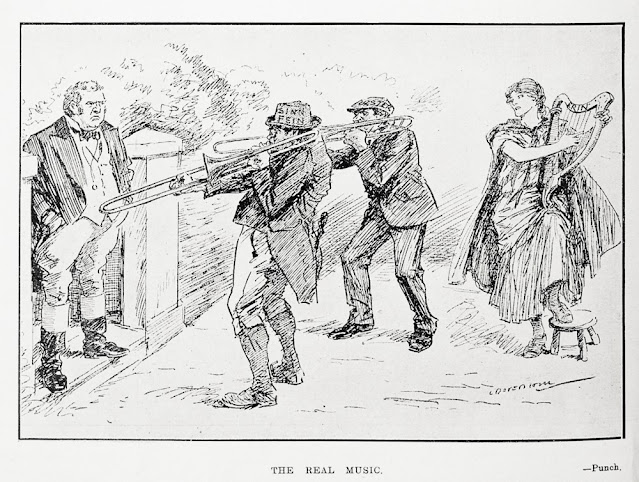

Northern Irish brawling between Sinn Féiners and Ulstermen distracted from all initiatives to peaceably settle the impasse. Our sixth cartoon (from Punch) shows rascals from both sides annoying John Bull with their trombones and rough music. In the background, another woman symbolizing Éireann strums her harp. John Bull says, ‘I wish they’d let me hear the lady.’ The implication is that squabbling and mayhem in Ulster prevents any possible settlement between British politicians and reasonable representatives from Southern Ireland. Yet again, the Irish depicted demonstrate their innate inability to settle their own political problems.

|

|

The mad nightmare of any future independent Ireland is imagined by the Punch cartoonist who drew our seventh cartoon. Prosperous Ulster farmer Jarvey’s horse-drawn wagon almost collides with Mick’s donkey cart. Jarvey tells Mick he’s on the wrong side of the road, but Mick answers, ‘Sure, the country’s our own now, and we can drive where we like.’ The shape of things to come? These days they actually do drive on the left in Éire!

Our eighth cartoon from

Punch is a political cartoon about the power of trade unions. The bricklayers’ union had imposed a work-speed limit, restricting the number of bricks that bricklayers could lay each hour. So the two bricklayers talking in the cartoon have expert opinions on whether the Government’s new housing bonds will lead to more houses being built. Not if the bricklayers’ union can hold things up …

Our ninth cartoon also comes from Punch. This time the arguing bricklayer has carelessly exceeded the union’s speed limit of 300 bricks per hour. The cartoonist obviously thinks that the union’s speed limit artificially slows the rate of work down, because bricklayers can demonstrably work faster than union rules allow.

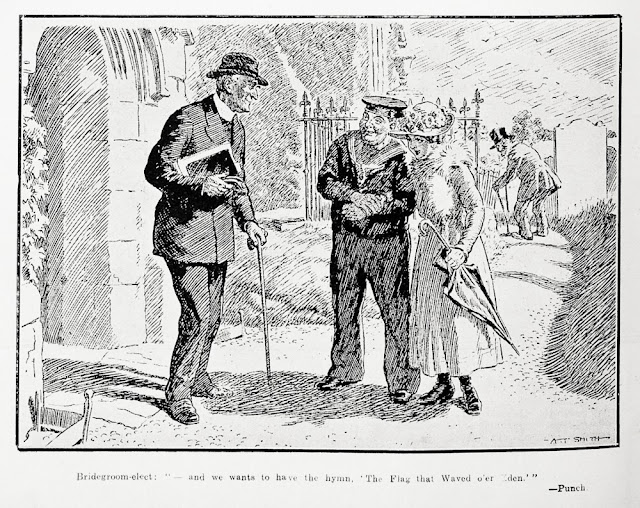

At first I had no idea what our tenth cartoon from

Punch was about. The only clue is the vicar’s cryptic smile. The sailor asks for a hymn entitled ‘The Flag that Waved o’er Eden,’ but the vicar knows there’s no such hymn. To get the punchline, you have to consult Hymns Ancient and Modern (the Anglican hymnbook) to find the hymn’s proper title, ‘The Voice that Breathed o’er Eden.’ The cartoonist seems to be commenting on the decline in churchgoing and religious knowledge in 1920, when younger people stayed away and the only parishioners were like the old man in the background!

Punch’s concern about the godless society is also reflected in our eleventh cartoon. In it a teacher reads ‘And Ruth walked behind the reapers, picking up the corn that they left.’ Contemporary readers would recognise she is a Sunday School teacher reading from the Book of Ruth in the Bible. However when she asks a boy what Ruth was doing, he naively says she was ‘pinching,’ not humbly accepting charity. Out of the mouths of babes and heathens!

Our twelfth cartoon is a humorous picture but also has some sort of implied moral. The motorcyclist’s girlfriend has fallen off his improvised pillion seat. Is the cartoonist’s implied message about the dangers of riding pillion and speeding on early 1920s motorcycles?

Our humorous thirteenth cartoon takes a swipe at well-meaning but patronising and misguided charity doled out to the deserving poor. Rich Lady Bountiful has dispensed quinine and port wine to a poor mother for her health complaints. She now checks on the progress of her patient. Dutiful daughter tells Lady Bountiful the quinine worked, but the port wine has made Mum’s drunkenness worse. The cartoon’s moral: Keep away from the Demon Drink!

Likewise, the

Punch cartoonist seems to be pointing out the wealth gap between the rich English upper class and the workers in our last cartoon about the penny-less rich. Having no pennies, the wealthy young lady gives the bus conductor half a crown (which was 30 pence.) The conductor assures her she’ll soon magically find another 29. Humour, but with a message…

Author: Christopher Paxton, Heritage Engagement

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.