Deforestation, drainage and development on the Hauraki Plains

As the explorers from HMS Endeavour rowed down the Waihou River in 1769, Captain James Cook imagined that Hauraki’s vast forests of tall, straight-trunked kahikatea could provide all the masts and spars England’s growing navy and mercantile marine would ever need. However, unbeknownst to Cook and his botanist, Joseph Banks, kahikatea would never be suitable for strong masts and spars. Because unlike kauri, the other tall and straight New Zealand hardwood which grows on drier ground, kahikatea grows in swampy wetlands. This means kahikatea wood is softer, and although initially hard when cut, soon dries out and becomes brittle.

|

| Image: Auckland Weekly News. Kahikatea bush at sunset, 1901. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. |

By the nineteenth century, Pākehā colonists realised this new ‘white pine’ was not the super-hard wonder wood early captains dreamt about, but found it was still useful for many building purposes. Then in 1882 New Zealand successfully exported its first cargo of refrigerated meat and dairy products to England. Suddenly there was a great demand for kahikatea’s white pine. Because the wood was soft, pale and odourless, kahikatea butter boxes and packing cases would not taint butter or dairy products. And so with an awfully predictable inevitability, by 1917 almost ⅔ of the vast kahikatea forests on the Hauraki Plains had disappeared. Thirty years later, only isolated stands of kahikatea remained on the plains.

|

| Image: Auckland Weekly News. A section of swampland on the bank of the Piako River awaiting drainage, 26 October 1922, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19221026-38-8. |

After the Hauraki Plains forests had been cut down, farmers settled on the newly cleared land. But once every year the Waihou and Piako Rivers would overflow. These yearly inundations were intensified because of the destruction of naturally draining wetland forest ecosystems. Periodical flooding and poor drainage made agricultural settlement of the Hauraki Plains difficult. The people who lived around Hauraki sought Government permission to drain the land, but the Government thought it could never be done because parts of the Hauraki Plains were two metres below sea level. However, in 1908 an act was passed allowing people to drain the land. The Government paid workers to dig the drains, a process that took ten years to complete.

|

| Image: New Zealand Department of Lands and Survey. Plan showing lands dealt with under the provisions of the Hauraki Plains Act, 1908, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, Map 4335. |

The Government’s Hauraki Plains Drainage Scheme sought to control the flooding of the Waihou River and drain the swamps of the Hauraki Plains. The Hauraki Plains Act 1908 and the Waihou and Ohinemuri Rivers Improvement Act 1910 provided the necessary legal machinery.

|

| Image: Auckland Weekly News. A closer view of the latest Rood dredge at work on the Hauraki Plains Drainage Scheme, 26 October 1922, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19221026-39-1. |

Contractors and labourers embarked on a colossal project building river and foreshore stopbanks and the Waitakaruru-Maukoro canal in the western Hauraki Plains.

Workers built stopbanks along the Piako River to keep it from overflowing, while around the Waihou River they dug a network of irrigation canals and drains. The workers installed pumping stations at regular intervals along the rivers and irrigation canals. Wharves were built at main settlements like Turua, Tahuna, Kaihere and Ngatea and these towns were connected by a network of roads and bridges.

|

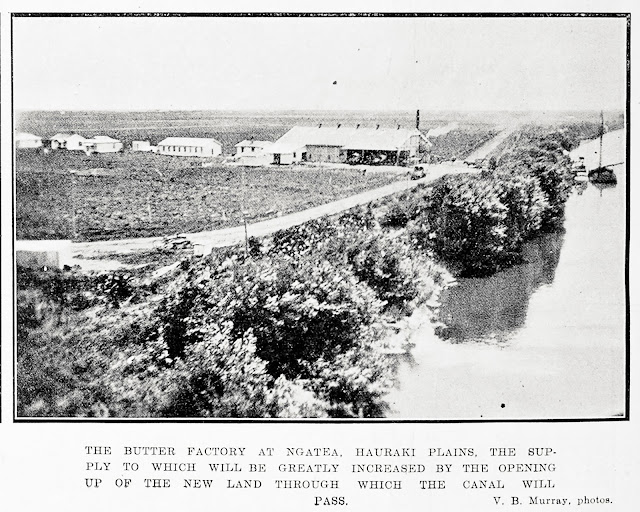

| Image: Auckland Weekly News. The butter factory at Ngatea, Hauraki Plains, 28 December 1922, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19221228-46-3. |

|

| Image: Auckland Weekly News. The Rood dredge operating at Kerepehi, 26 October 1922, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19221026-38-6. |

By 1910, 66 square kilometres of drained and reclaimed land was opened up for settlement in the upper Hauraki Plains between Kopuarahi and Ngatea. This new farmland was made available to settlers through a ballot system. Then between 1910 and 1914 more than 15,000 hectares southwest of Waitakaruru was drained and distributed to a further 270 settlers.

|

| Image: Auckland Weekly News. The latest 45-horsepower Caterpillar dredge at work deepening the Piako River, 17 August 1922, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19220817-41-4. |

Between 1919 and 1923, the period from which these 1922 photographs date, Government drainage work was continuing south of Kerepehi. The Crown worked on its Hauraki Plains Drainage Scheme until 1942, completing its network of drained land for new balloted farms between Ngatea and Netherton.

But the Waihou and Piako rivers still flooded each year. This meant farmers still had to dig and maintain irrigation channels through their land. These channels connected to the main drains, from which the water flowed into the canals. As a result of the drainage system, which included floodgates stopping water from seeping back into drained land, the size of the wetlands declined to less than a quarter of their original area.

After their land had drained and dried, farmers cleared and burned scrub, logs and tree stumps. Then they had to level the land and convert it to pasture. However, they soon discovered they had to battle continual infestations of tall fescue ‘quack’ grass, which could cause stock losses. And their farmland turned rock hard in summer droughts and still became waterlogged during the winter rains.

In the riverine environment of the Hauraki Plains, boats and barges were the most effective way to transport goods, people and animals in the early days before an effective road network was developed. In the early twentieth century, it was still possible to sail down the Waihou River as far inland as Matamata.

|

| Image: Auckland Weekly News. Settlers unloading stores on the banks of the Piako River at Tahuna, 26 October 1922, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19221026-38-4. |

Ships of all sizes, from rowboats to large barques plied the rivers of the Hauraki Plains. Barques could navigate down the Waihou River as far inland as Turua, where they loaded cargoes of kahikatea planks from Bagnall’s sawmill destined to be made into Australian butter-boxes.

However most ships on the Hauraki Plains rivers were locally built steamers fitted with engines built by A. & G. Price in Thames.

|

| Image: Auckland Weekly News. The river steamer on the Piako River near Tahuna, 26 October 1922, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19221026-38-2. |

Sailing inland from Pipiroa down the Piako River, ships passed Ngatea then Kerepehi. After reaching Kaihere, the Piako was navigable as far inland as Patetonga.

|

| Image: Auckland Weekly News. A busy scene in the early morning at Kaihere Landing, 26 October 1922, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19221026-38-5. |

|

| Image: Auckland Weekly News. In the centre of the Hauraki Plains district. A barge conveying stores on the Piako River, 26 October 1922, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19221026-38-1. |

The lost kahikatea forests and wetlands of Hauraki’s distant past have today been transformed into the dairy farm landscape that now predominates on the plains. These days, cow effluent and fertiliser runoff endanger water quality and contribute to further silting up the Hauraki Plains rivers and waterways.

Author: Christopher Paxton, Heritage Engagement

Further reading:

Toni Hartill, ‘Artful narratives and the destruction of the kahikatea forests,’ HeritageEt al, http://heritageetal.blogspot.com/2022/03/artful-narratives-and-destruction-of.html

Malcolm McKinnon, ed., Bateman New Zealand Historical Atlas: Ko Papatuanuku e Takoto Nei. Auckland, 1997.

Paul Monin, 'Hauraki–Coromandel region - Drainage and dairying on the plains', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/hauraki-coromandel-region/page-9 (accessed 21 March 2023)

Geoff Park, Ngā Uruora: Ecology and History in a New Zealand landscape. Wellington, 1995.

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.