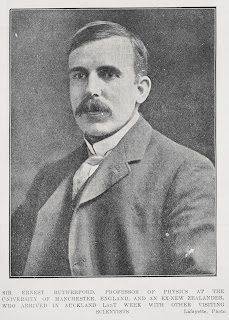

Sir Ernest Rutherford

It was sixty-six years ago this month that Nobel prize winner Ernest (Ern) Rutherford (1871-1937), the "father of nucelar physics" passed away. He was interred in Westminster Abbey, surrounded by the ashes of scientists such as Sir Isaac Newton. Rutherford was 66 when he died. Following his death an obituary in the New York Times said, "It is given to but few men to achieve immortality, still less to achieve Olympian rank, during their own lifetime. Lord Rutherford achieved both.”

Despite his intellectual achievements, Rutherford, or Ern as he was called, was said to be a humble man. Physically, he was large, and quite the talker. He had a tendency to spill his tea on his waistcoat, to which wife, Mary, would proclaim, “Ern, you’re dribbling.” Mary had marched with the suffragettes in London and not surprisingly, Ern was a huge supporter of women studying the sciences. His very first research assistant, Harriet Brookes, assisted him in the discovery of radon while at McGill University in Montreal. British biochemist Marjorie Stephenson recalled meeting him when she was a young girl, where he asked her to promise she would become a scientist. She did, and became one of the first two women to be a fellow of the Royal Society. In 1920, he wrote a letter to The Times to ask his fellow academics to give women at Cambridge the same rights as men.

A passion for the sciences followed in his family, too. His only child, Eileen (who died tragically just days after the birth of her fourth child) had married Ralph Fowler, a mathematical physicist. All four of the Fowler children went in to the sciences including their two daughters; Elizabeth became a doctor, and Ruth a research physiologist. Ruth’s husband, Professor Robert Edwards, won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2010.

Rutherford’s work, however, extended far beyond the laboratory. He helped found the Academic Assistance Council, which helped displaced academics from Europe in one of the biggest mass migrations of scientists the world had seen, which also shifted the scientifc center from Europe to America. He had once stated he hoped the method for extracting atomic energy wouldn’t be discovered until man was at peace with his neighbours; nuclear fission was discovered two years after his death.

Respect for him was universal, throughout his life and after his death. He appeared on postage stamps in Sweden (1968), Canada, the USSR, New Zealand (1971), is the face on the New Zealand one hundred dollar note and in 1969 the element 104 was named rutherfordium in his honour. Although he was awarded a Nobel Prize, he is most famous for splitting the atom – which he did a decade after his Prize in chemistry. He was knighted in 1914, and in 1931, he was elevated into the peerage - Ernest, Lord Rutherford of Nelson.

While Ernest is remembered in so many ways, if you happen to ever chance across the town of Brightwater (formerly Spring Grove) Nelson, you will find a stunning memorial to him where State Highway 6 meets Lord Rutherford Road. Although the Rutherford family moved often in Ernest’s childhood, Spring Grove was the place where Sir Ernest was born.

For insights into Rutherford’s Cambridge days, Auckland Libraries has copies of 'Rutherford: Recollections of the Cambridge Days' by Mark Oliphant. Oliphant (Sir Mark Oliphant) knew both Lord and Lady Rutherford personally, and opened the Spring Grove memorial in 1991. A new book entitled 'Mad on radium : New Zealand in the atomic age' by Rebecca Priestley will also of interest.

For more information, check out biographer John Campbelll's website on Rutherford, which includes a great selection of images.

Author: Joanne Graves, Central Auckland Research Centre

Despite his intellectual achievements, Rutherford, or Ern as he was called, was said to be a humble man. Physically, he was large, and quite the talker. He had a tendency to spill his tea on his waistcoat, to which wife, Mary, would proclaim, “Ern, you’re dribbling.” Mary had marched with the suffragettes in London and not surprisingly, Ern was a huge supporter of women studying the sciences. His very first research assistant, Harriet Brookes, assisted him in the discovery of radon while at McGill University in Montreal. British biochemist Marjorie Stephenson recalled meeting him when she was a young girl, where he asked her to promise she would become a scientist. She did, and became one of the first two women to be a fellow of the Royal Society. In 1920, he wrote a letter to The Times to ask his fellow academics to give women at Cambridge the same rights as men.

|

| Ref: AWNS-19140910-48-5, Sir George Grey Special Collections |

Rutherford’s work, however, extended far beyond the laboratory. He helped found the Academic Assistance Council, which helped displaced academics from Europe in one of the biggest mass migrations of scientists the world had seen, which also shifted the scientifc center from Europe to America. He had once stated he hoped the method for extracting atomic energy wouldn’t be discovered until man was at peace with his neighbours; nuclear fission was discovered two years after his death.

|

| Ref: AWNS-19280531-46-5, Sir George Grey Special Collections |

While Ernest is remembered in so many ways, if you happen to ever chance across the town of Brightwater (formerly Spring Grove) Nelson, you will find a stunning memorial to him where State Highway 6 meets Lord Rutherford Road. Although the Rutherford family moved often in Ernest’s childhood, Spring Grove was the place where Sir Ernest was born.

For insights into Rutherford’s Cambridge days, Auckland Libraries has copies of 'Rutherford: Recollections of the Cambridge Days' by Mark Oliphant. Oliphant (Sir Mark Oliphant) knew both Lord and Lady Rutherford personally, and opened the Spring Grove memorial in 1991. A new book entitled 'Mad on radium : New Zealand in the atomic age' by Rebecca Priestley will also of interest.

For more information, check out biographer John Campbelll's website on Rutherford, which includes a great selection of images.

Author: Joanne Graves, Central Auckland Research Centre

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.