Quran

Among the many items that Auckland bibliophile Henry Shaw (1850-1928) donated to the Library early in the twentieth century are a number of Asian and Middle Eastern manuscripts purchased from London booksellers. Shaw did not share Sir George Grey's interest in philology. His chief reason for collecting these manuscripts was aesthetic rather than linguistic. He was drawn to fine calligraphy and illustration.

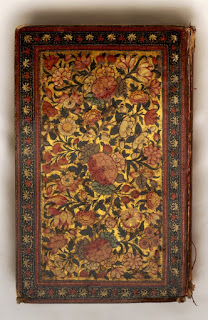

One of Shaw's most exquisite donations is a handwritten Quran from India, bound in lacquered paiper-mâché covers that are painted on both sides with richly coloured floral patterns. The sacred text is inscribed in black ink on a gold background within blue and gold borders. Chapter headings are written in blue and accompanied with small ornamental devices. Many pages have skillful decorations in the margins.

On one of the pages Shaw has pasted a note from a bookseller's catalogue (probably J. and J. Leighton's), dating the manuscript about AH 1230 in the Islamic calendar. This translates to AD 1817 in the Gregorian calendar - a turbulent year in Indian history, with the British Army, commanded by governor general Rawdon-Hastings, Earl of Moira, engaged in protracted (and ultimately victorious) warfare with the forces of the Maratha Empire. It is not known, however, where or under what circumstances the manuscript was compiled. Dr Zain Ali, head of Islamic studies at the University of Auckland and the Auckland Library Heritage Trust 2014/15 Researcher in Residence at Sir George Special Collections, speculates that the Quran was a product of a Mughal court.

Non-Muslims may wonder why an Indian Quran should be written in Arabic rather than Urdu. In the Islamic world it is believed that the divine word of God, as revealed to the Prophet, assumed a specific, Arabic form that cannot be translated into other languages without losing crucial layers of meaning. For Muslims, a translation of the Quran is not the Quran itself - just an interpretation.

Similar in length to the New Testament, the Quran is divided into chapters, known as Suras, which vary in duration from ten words to 6100. The Suras are further divided into short passages, each of which is called an aya. Although this term is often translated as 'verse', the literal meaning is 'sign'. In the manuscript gold circles mark the beginning and end of each aya.

The Quran and associated Arabic manuscripts are on display in the Sir George Grey Special Collections reading room on Level 2 of Central City Library daily to 5pm until Saturday 13 June.

Information from Real Gold by Iain Sharp, Sir George Grey Special Collections.

One of Shaw's most exquisite donations is a handwritten Quran from India, bound in lacquered paiper-mâché covers that are painted on both sides with richly coloured floral patterns. The sacred text is inscribed in black ink on a gold background within blue and gold borders. Chapter headings are written in blue and accompanied with small ornamental devices. Many pages have skillful decorations in the margins.

On one of the pages Shaw has pasted a note from a bookseller's catalogue (probably J. and J. Leighton's), dating the manuscript about AH 1230 in the Islamic calendar. This translates to AD 1817 in the Gregorian calendar - a turbulent year in Indian history, with the British Army, commanded by governor general Rawdon-Hastings, Earl of Moira, engaged in protracted (and ultimately victorious) warfare with the forces of the Maratha Empire. It is not known, however, where or under what circumstances the manuscript was compiled. Dr Zain Ali, head of Islamic studies at the University of Auckland and the Auckland Library Heritage Trust 2014/15 Researcher in Residence at Sir George Special Collections, speculates that the Quran was a product of a Mughal court.

Non-Muslims may wonder why an Indian Quran should be written in Arabic rather than Urdu. In the Islamic world it is believed that the divine word of God, as revealed to the Prophet, assumed a specific, Arabic form that cannot be translated into other languages without losing crucial layers of meaning. For Muslims, a translation of the Quran is not the Quran itself - just an interpretation.

Similar in length to the New Testament, the Quran is divided into chapters, known as Suras, which vary in duration from ten words to 6100. The Suras are further divided into short passages, each of which is called an aya. Although this term is often translated as 'verse', the literal meaning is 'sign'. In the manuscript gold circles mark the beginning and end of each aya.

The Quran and associated Arabic manuscripts are on display in the Sir George Grey Special Collections reading room on Level 2 of Central City Library daily to 5pm until Saturday 13 June.

Information from Real Gold by Iain Sharp, Sir George Grey Special Collections.

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.