No description is equal to an actual leaf

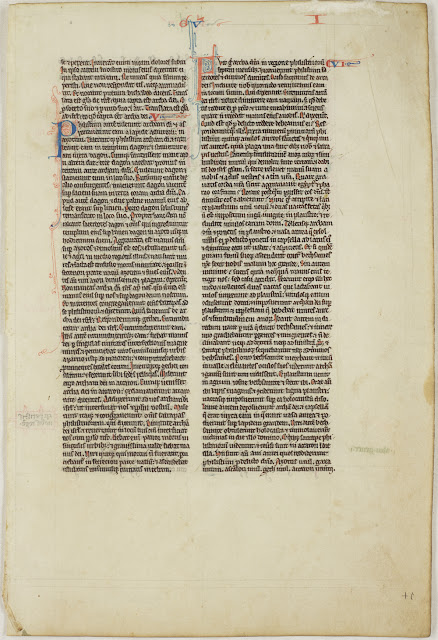

On display during March 2017, in the Special Collections reading room at the Auckland Central City Library, is a single leaf from a 13th century Latin Bible generously donated to the Library by Keith Stuart in 2016.

Stuart, an archivist trained in biblical research presented a paper to ANZBS Conference in 2010 which included a detailed description of the leaf.

Described as a typical leaf from a Paris manuscript bible, it is roughly the same size as a sheet of A4. This is much larger than a Bible we may be familiar with viewing, but it is not especially large for a medieval Bible. As Stuart notes, the size of Bibles became smaller with the rise of Mendicant orders and their travelling preachers, so portability became important.

The text is in Latin, from Saint Jerome’s translation of the Hebrew and is from the first book of Kings, chapter 4 verse 19 to chapter 8 verse 22. It tells of the Ark of the Covenant in Philistine through to Israel’s demand for a King.

The leaf provides a significant example of a leaf from a thirteenth century Bible. It is hand written in a small gothic script on thin vellum. The thinness of the vellum can be seen in the text showing through from the other side. It also reflects the artistry of books of the period contrasting coloured lettering and fine pen work.

The purchase of single leaves or fragments from medieval manuscripts dates back centuries, following on from the trade in ecclesiastical relics. Stuart purchased this leaf from Paulus Swaen Old Maps and Prints, a reputable dealer, who claim to be the first internet auction house specialising in prints, maps and medieval manuscripts. Assurances of authenticity have been sought from rare book dealers and antiquarians since the beginning of the trade, as Christopher de Hamel writes. Medieval relic collectors felt the same need for assurance around authenticity (Disbound and dispersed, p.22).

Author: Andrew Henry

Stuart, an archivist trained in biblical research presented a paper to ANZBS Conference in 2010 which included a detailed description of the leaf.

Described as a typical leaf from a Paris manuscript bible, it is roughly the same size as a sheet of A4. This is much larger than a Bible we may be familiar with viewing, but it is not especially large for a medieval Bible. As Stuart notes, the size of Bibles became smaller with the rise of Mendicant orders and their travelling preachers, so portability became important.

The text is in Latin, from Saint Jerome’s translation of the Hebrew and is from the first book of Kings, chapter 4 verse 19 to chapter 8 verse 22. It tells of the Ark of the Covenant in Philistine through to Israel’s demand for a King.

The leaf provides a significant example of a leaf from a thirteenth century Bible. It is hand written in a small gothic script on thin vellum. The thinness of the vellum can be seen in the text showing through from the other side. It also reflects the artistry of books of the period contrasting coloured lettering and fine pen work.

Fragments will often be traded as they are but sometimes

this trade involves the breaking-up of larger works. Breaking-up a complete work is

frowned upon by book collectors, but given the age of these items sometimes

only an incomplete work will survive. Often a seller will gain a far

greater profit by breaking-up the incomplete text and selling it leaf by leaf.

This practice is illegal in Italy, where there is legislation in place

protecting cultural properties including manuscripts, documents and books.

In the case of rare books, a niche genre has been created

through the breaking-up of books: the leaf

book. Bibliographer Francis Fry, who created the first generally recognised

leaf book, provides the title to this blog post. There is a moral conundrum

over the breaking up of rare books and manuscripts. Fry encapsulates one side

of the argument for which the goal was to enable as many people as possible to

enjoy these fragments. The other side of the argument is that breaking-up books

is nothing short of vandalism as it destroys the original book and it leads to

a loss of information around the provenance, binding and historical context of

the publication. It seems unbelievable today but one leaf book was even created

from an incomplete copy of a Gutenberg Bible.

De Hamel notes that leaf books have not been as popular for

medieval manuscripts because exact dating of manuscripts is very

difficult.

In addition to this leaf on display, Auckland Libraries

holds the largest and most diverse collection of medieval manuscripts in New

Zealand. Digital versions of a number of these are accessible via the Manuscripts Online

database.

Further reading:

- Disbound and dispersed : the leaf book considered / Christopher de Hamel, Joel Silver

- Keith Stuart's ANZBS paper is available on request from the Manuscript Librarian at Special Collections, Auckland Central City Library.

Author: Andrew Henry

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.