The price of progress

The way some individuals and companies exploit our environment seems to be a very twenty-first century concern. However, photographs published in the New Zealand Graphic one hundred years ago show people were starting to realise New Zealand’s natural landscape and resources had been seriously degraded by extractive nineteenth-century industries and farming techniques.

On 6 May 1893 the New Zealand Graphic published a photo with the stark caption, ‘Our timber trade: the work of destruction in a kauri forest.’ It showed a jumbled mass of logs already felled by bushmen. Bullock teams were being harnessed to drag the logs from the forest; probably to a bush tramway and then to a sawmill.

|

| Ref: Martin. Our timber trade, the work of destruction in a Kauri forest, 6 May 1893. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-18930506-409-1 |

Sixteen years later in 1909 the Graphic published a page of photos entitled simply ‘How the Dominion bush is vanishing.’ The series showed a doomed kauri tree’s final journey from the forest via bullock team, bush tramway and log dam towards the city sawmill.

Indeed, the New Zealand timber industry’s insatiable appetite for kauri meant logging companies had to go to increasingly extreme lengths to exploit the only remaining stands of kauri. These trees were usually in relatively inaccessible areas which was the reason why they had survived so long. The next photo shows extreme efforts to log kauri near Kaihu in Northland, where the bushmen had to build an aerial tramway through the bush to get at the last kauri left.

The Graphic’s photo caption describing the Kauri Timber Company’s enterprise to extract another twenty million feet of timber from the Waitawheta Gorge near Owharoa summarises it all: ‘Owing to the growing scarcity of kauri timber, forests are now being worked which a few years ago would not have been looked at.’ The company was so desperate to get at the timber it installed an expensive, powerful steam winch to control heavy wagons of kauri logs as they rolled down the steep Owharoa incline to a junction with the main trunk railway.

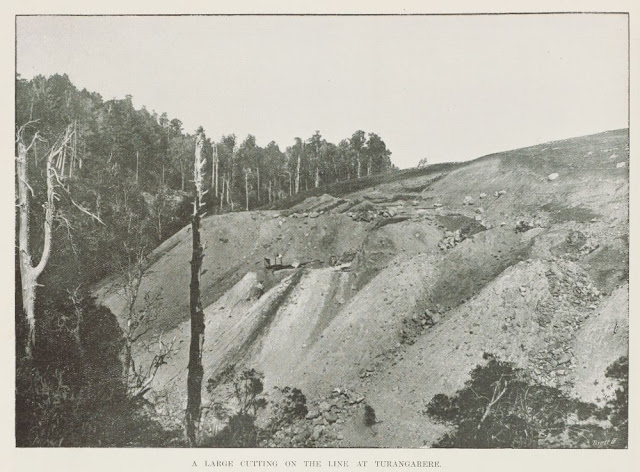

More deforestation occurred in the North Island as the main trunk railway line was built between Auckland and Wellington. This panoramic photo taken near Turangarere shows the extent of the land cleared from the forest (on the left) wherever the railway tracks had to go through.

Some of the logs cleared for the main trunk line could be put to good use. Some logs were taken to a sawmill at Kakaki, where totara, rimu and kahikatea were sawn up for sleepers, bridges or use in general railway construction.

Often after the logging companies’ had been through the forests logging usable trees, settlers burned off much of the remaining bush and scrub, before breaking the land into farm paddocks. In 1900 the Graphic published one of Charles Peet Dawes’s photos captioned ‘After the bushman and fire have passed through.’

On 21 January 1893 the Graphic published a page showing two New Zealand bush sketches. The upper sketch showed a mountain track and the lower sketch showed a similar area from a slightly different angle, with the thought-provoking caption ‘Forest giants after the fire.’

By the 1900s some people realized there was a correlation between deforestation and soil erosion caused by flooding. On 16 June 1909 the Graphic published a series of photos from Manawatu showing land washed away when cleared pastureland had no plant cover to help bind soil or absorb river water.

The next year, on 8 June 1910, the Graphic further highlighted the inverse relationship between receding forests and the advance of water, when the paper published an aerial panorama of flooding at Te Aroha. This happened because floodplains around the Ohinemuri and Waihou rivers had been cleared of forest and the land turned into farm paddocks. There was no natural plant cover to absorb overflowing river water, and the floodwaters spread out as we see in the picture.

These are just some photographic examples from the extensive New Zealand Graphic coverage of the degradation of New Zealand’s native bush in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Author: Christopher Paxton, Heritage Collections

|

| Ref: New Zealand Graphic. How the Dominion bush is vanishing, 19 May 1909, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19090519-17-1. |

Then in 1910 the paper published a photo of two bushmen posing by a tall and massive kauri they are in the process of cutting down. While the photo was captioned ‘Food for the mills – the end of a majestic kauri,’ inset in the picture is the single word ‘Doomed,’ which by this time summed up the perilously marginal existence of any areas of kauri forest left in New Zealand.

|

| Ref: Northwood. Food for the mills: the end of a majestic kauri, 16 November 1910, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19101116-17-1. |

Indeed, the New Zealand timber industry’s insatiable appetite for kauri meant logging companies had to go to increasingly extreme lengths to exploit the only remaining stands of kauri. These trees were usually in relatively inaccessible areas which was the reason why they had survived so long. The next photo shows extreme efforts to log kauri near Kaihu in Northland, where the bushmen had to build an aerial tramway through the bush to get at the last kauri left.

|

| Ref: New Zealand Graphic. Cutting out kauri near Kaihu, in North Auckland, 7 December, 1910, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19101207-32b-3 |

The Graphic’s photo caption describing the Kauri Timber Company’s enterprise to extract another twenty million feet of timber from the Waitawheta Gorge near Owharoa summarises it all: ‘Owing to the growing scarcity of kauri timber, forests are now being worked which a few years ago would not have been looked at.’ The company was so desperate to get at the timber it installed an expensive, powerful steam winch to control heavy wagons of kauri logs as they rolled down the steep Owharoa incline to a junction with the main trunk railway.

|

| Ref: New Zealand Graphic. Where twenty million feet of timber will be obtained, 16 November 1910, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19101116-25-1 |

More deforestation occurred in the North Island as the main trunk railway line was built between Auckland and Wellington. This panoramic photo taken near Turangarere shows the extent of the land cleared from the forest (on the left) wherever the railway tracks had to go through.

|

| Ref: New Zealand Graphic. A large cutting on the line at Turangarere, 29 April 1905, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19050429-34-1. |

Some of the logs cleared for the main trunk line could be put to good use. Some logs were taken to a sawmill at Kakaki, where totara, rimu and kahikatea were sawn up for sleepers, bridges or use in general railway construction.

|

| Ref: Hawkins. The progress of the North Island main trunk railway, 29 July 1905, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19050729-31-1 |

After the main trunk line was completed, work started on a railway line from Ōngarue to Stratford so that Taranaki farmers and businesses could get access to Auckland markets. On 21 September 1910 the Graphic published two interesting photos showing ‘How deforestation follows the railway’ (or actually just precedes it). The photos have an inset caption, ‘Two sides of the tunnel.’ The upper photo shows the forest cleared from the railway where the line from Stratford goes through a tunnel in the Pohukura Saddle. The lower photo shows land two miles further on towards Pohukura beyond the tunnel, showing the line’s planned direction through untouched forest.

|

| Ref: Axel Newton. How deforestation follows the railway, 21 September 1910, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19100921-18-1 |

Often after the logging companies’ had been through the forests logging usable trees, settlers burned off much of the remaining bush and scrub, before breaking the land into farm paddocks. In 1900 the Graphic published one of Charles Peet Dawes’s photos captioned ‘After the bushman and fire have passed through.’

|

| Ref: Charles Dawes. After the fire and bushman have passed through, 17 February 1900, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19000217-300-4 |

Then on 23 January 1904 the paper published a dramatic photo of a burn-off in progress, with rolling clouds of smoke hanging over a blasted landscape of skeletal trees and stumps.

|

| Ref: New Zealand Graphic. Burning-off, 23 January 1904, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19040123-41-3. |

This photo must have impressed the editors so much they appear to have re-published it in their 12 May 1909 issue, albeit with an apposite and profound new caption: ‘The growth of centuries vanishing in smoke and flames.’

|

| Ref: New Zealand Graphic. The growth of centuries vanishing in smoke and flames, 12 May 1909, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19090512-25-3 |

On 21 January 1893 the Graphic published a page showing two New Zealand bush sketches. The upper sketch showed a mountain track and the lower sketch showed a similar area from a slightly different angle, with the thought-provoking caption ‘Forest giants after the fire.’

|

| Ref: New Zealand Graphic. New Zealand bush sketches, 21 January 1893, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-18930121-58-1. |

By the 1900s some people realized there was a correlation between deforestation and soil erosion caused by flooding. On 16 June 1909 the Graphic published a series of photos from Manawatu showing land washed away when cleared pastureland had no plant cover to help bind soil or absorb river water.

|

| Ref: New Zealand Graphic. This cliff on the Manawatu... 16 June 1909, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19090616-24-1. |

|

| Ref: New Zealand Graphic. A valuable scenic reserve at Palmerston North on the banks of the Manawatu... 16 June 1909, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19090616-25-1 |

|

| Ref: Whalley & Co. A typical scene on the Manawatu demonstrating the effects of the periodic floods... 16 June 1909, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19090616-25-2 |

|

| Ref: Belcher. The results of deforestation, 8 June 1910, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZG-19100608-26-2 |

These are just some photographic examples from the extensive New Zealand Graphic coverage of the degradation of New Zealand’s native bush in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Author: Christopher Paxton, Heritage Collections

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.