Transcription tales: Rev. Benjamin Ashwell and the mission school at Kaitotehe

During the COVID-19 lockdown, I have been transcribing Grey New Zealand Letters and was tasked with working on letters by authors whose surname begins with the letter 'A'. This includes 10 letters by Rev. Benjamin Yate Ashwell (1810-1883) spanning 1849-1871 (GLNZ A13.1-A13.10). Ashwell wrote these letters to Sir George Grey (1812-1898) who was twice governor of New Zealand, first from 1845-1853 and again from 1860-1868. All the letters that I, and my colleagues have been working on, are digitised and available via Manuscripts Online. The transcription work we are doing will not only assist with online searches but will help you read the letters, since nineteenth century script and abbreviations can be frustrating at times to read!

Ashwell was born in Birmingham, England and trained with the Church Missionary Society in London (1831-1833). He spent a few years as an Anglican lay missionary in West Africa before emigrating in 1835 to New Zealand. Between 1839 and 1842 he helped Rev. Robert Maunsell (1810-1894) establish a mission station at Maraetai, Waikato Heads. Graduating from these duties, Ashwell set up and ran a mission station in the Waikato (1843 to 1863). Ashwell did not forget his missionary colleague though and remained in contact with him, mentioning him often in his letters to Grey.

The mission station Ashwell ran was located a short distance from the rear of the pā at Kaitotehe. The pā had been built at the foot of the sacred mountain, Mount Taupiri, by King Pōtatau Te Wherowhero (?-1860), paramount chief of the Waikato tribes. Kaitotehe lay on the flat and fertile land of the west bank of the Waikato River, opposite the settlement of Taupiri and within close vicinity of Ngāruawāhia. From this location, Ashwell was responsible for a large district of around 70 miles, comprising thirty villages and extending as far as Port Russell. Despite not having very robust health, Ashwell’s already busy working life was also occupied with running the mission station’s school for Māori children. Under his direction and indefatigable energy, the school grew and developed. From a colonial perspective it was successful (up until the war in the Waikato), leading Cowan to describe it as the “centre of religion and secular learning on the mid-Waikato” (1934: 21).

Ordained by Bishop George Augustus Selwyn, Ashwell is described as being temperamental and eccentric. Despite this he was influential and respected by the Waikato Māori, who called him Te Ahiwera or Hot Fire. He was not, however, supportive of the growing Kīngitanga (King) movement in the area and his letters are full of references to the growing unrest. When war broke out in the Waikato in 1863, he evacuated to Auckland. Based at Trinity Church in Devonport from 1866, he ran the Parish of the Holy Trinity, which at the time incorporated all of the North Shore. Whilst in this role, he also continued working as a missionary with Māori, holding a “Maori Service once a month at the Lake” (located between the suburbs of Takapuna and Milford), as well as working with communities in North Mahurangi and Te Muri (1871, GLNZ A13.10). After working again in the Waikato during the 1870s, he permanently returned to Auckland. He retired in 1883, ending a missionary career of over 49 years.

The mission station at Kaitotehe was much drawn, painted and later photographed, including by the painter George French Angus (see above) and photographer Bruno L. Hamel (see further on). The latter visited the area in 1859, as part of the Government Scientific Exploring Expedition conducted by Dr. Ferdinand Hochstetter (see photographs further on). In addition to impressions showing the whole mission station, artists and photographers also focused on capturing specific elements. This included not only the school but also the church, which combined both Māori and Gothic Revival architectural elements, as seen in the sketch below. Hochstetter described the church as “a pretty specimen of a Maori building” and noted “its door-posts and gable-beams [were] gayly painted” (1867: 308).

Schooling at the mission was conducted in a "highly finished and ornamental weatherboarded house" containing a central school room, dining room and dormitory (New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian, 14 September 1853). It is this mission school, that was the subject of many of Ashwell’s letters to Grey during the 1850s. Although Grey does not appear to have visited the school until January 1863, as the war in the Waikato was beginning to ignite, he was, however, pivotal in establishing and setting the tone for Māori education policies during the 19th century and well into the next. Grey believed in colonial theories of ‘civilisation’ and racial amalgamation (retaining and combining the most desirable aspects of European and Māori culture), although the affect was more akin to assimilation (ensuring Māori learnt European ways). Central to achieving these goals was his approach to education policy and for this he consulted with Rev. Maunsell, who was considered an authority on Māori education. Accordingly, when first in office Grey established the Education Ordinance 1847 to support Anglican, Roman Catholic and Wesleyan mission schools throughout New Zealand with public funds. This policy was founded on instruction in religion, the English language and training in manual and domestic skills, and was officiated by government inspectors. The later Native Schools Act 1858, which provided subsidies for ‘native’ mission boarding schools, was also based on these principles but additionally required Māori children to board on site.

Ashwell references Grey’s involvement in education policy when he wrote to him in 1852, stating "[k]nowing the interest which you take in the formation of Schools for the instruction of the Aborigines I take the liberty of bringing under your notice the present position and prospects of the School at Kaitotehe" (25 November 1852, GLNZ A13.4). Over the years of their correspondence, Ashwell informed Grey about the growing numbers of pupils at Kaitotehe. This was perhaps as a less informal way of reporting on the mission school’s progress, although Ashwell was also an officially licensed inspector. For example, in 1850 Ashwell states that the number of pupils had risen to around 30-40 (24 May 1850, GLNZ A13.2). Less than two years later, he is pleased to report the number of pupils had nearly doubled to “sixty[,] chiefly girls" (27 December 1852, GLNZ A13.5). By the time Hochstetter visited in 1859, it had risen again to 94 pupils, consisting of 46 girls and 48 boys (1867: 307-308).

Although Ashwell does not describe the daily routines of school life in his letters to Grey, he does elaborate on this in Recollections of a Waikato Missionary:

“The rules were as follows:-- An hour before breakfast--6 a.m. in summer, 7 a.m. in winter--the bell rang: prayers and Bible-class for an hour; this I always took. 8 a.m. in summer, and 9 a.m. in winter, the bell rang for breakfast. 9 a.m. in summer, and 10 a.m. in winter, the bell rang for school. 1 p.m., dinner. 2 p.m., the sewing-school for girls, and farm work for boys, till 5 p.m. At 6 p.m., tea. After tea, the elder girls were engaged knitting, and the others in a reading class. Our usual course of instruction was reading, in native and English grammar, geography, history, writing, arithmetic, and singing …” (Ashwell, 1878: 20).

As the rules outline, there was a close adherence to the Education Ordinance fund regulations. This included foci on literacy and religious studies, as well as gendered activities for the pupils (as was typical of the time); namely indoor household work for the girls and outdoor farming for the boys. The latter is also revealed by Hochstetter’s description of the school during his visit. He observed that “Maori girls, who are here instructed in different branches of domestic work, while the boys are trained for agriculture and all sorts of useful trades” (Hochstetter, 1867: 309).

Despite Grey's departure from New Zealand in late 1853, to take on the post of governor of Cape Colony (South Africa), Ashwell continued to advise him about schooling in the Waikato and ask for assistance. In 1855, for example, he writes:

"I feel assured that your Excellency still feels an interest in the progress of Education amongst the Aborigenes [sic] of New Zealand. The Waikato Schools I believe are still progressing. Mr Maunsell Number 80 Scholars Mr Morgans 30 Half Castes & Native and Taupiri 52". (GLNZ A13.8, 1 September 1855).

The school was supported by annual government funding of around £100 through the Education Ordinance fund, but by 1852 the school was in debt. Ashwell relayed this to Grey explaining "[i]n 1850 I erected a large School House containing three rooms on one wing of mine own dwelling. This Building cost £280, and for its erection I received £50 from the Government Grant, and no other assistance" (24 November 1852, GLNZ A13.4). Further on in the letter, Ashwell catalogues the costs of running the school, describing how this often resulted in shortfalls. This was despite taking on boarders from 1846 and seeking other forms as revenue, such as mats woven by the female pupils. He notes:

"We have maintained, an average number of 50 Boarders, during the last three years and for their support have received only £100 per annum, from Government Grant, besides these scholars we board and pay an English Female Assistant. We are now more than £300 in debt. The question has now been forced on my attention whether I should not considerably diminish the number of scholars. This step I should deeply regret …" (ibid.).

Grey responded to Ashwell's request for assistance by sending him £100 towards the costs (27 December 1852, GLNZ A13.5). As this and other letters show, Grey played an important role in supplementing the school’s funding.

Something which we can identify with today, is the cost of food. Ashwell advised Grey in 1852 that he feared "food rising in price in consequence of the late discovery of gold in this Hemisphere" (24 November 1852, GLNZ A13.4). This comment is probably in reference to Charles Ring’s discovery of a small amount of gold near Coromandel town in 1852. As a solution, Ashwell informed Grey that he had bought around 100 acres of land, located 2 miles away, with the intention of enabling the mission station to be self-sufficient. In outlining his plans, he strategically appealed to Grey to help finance this endeavour:

"Revd. R Maunsell has undertaken that his school should plough and harrow it for us. For his preliminary operation, we need between £30 & 50, and my object now is to solicit this assistance from your Excellency. I forbear enlarging on the advantages which I expect to result to us from this undertaking. I am aware that your Excellency has more than once expressed strong opinions, upon the desirableness of helping Institutions to gain their own support, and I indulge strong hopes that the economical way in which the aid hitherto gained to us has been expended will induce your Excellency if possible to grant us the aid so much needed, at this juncture" (24 November 1852, GLNZ A13.4).

|

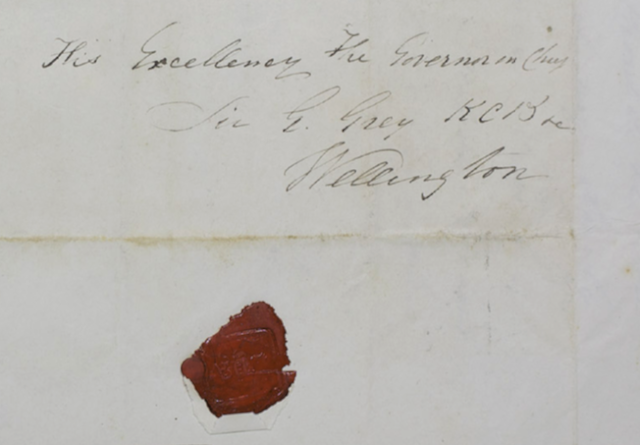

| Envelope with seal and letter from Rev. Benjamin Ashwell to Sir George Grey. 27 December 1852. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, GLNZ A13.5. |

|

| Envelope with seal and letter from Rev. Benjamin Ashwell to Sir George Grey. 27 December 1852. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, GLNZ A13.5. |

Ashwell was born in Birmingham, England and trained with the Church Missionary Society in London (1831-1833). He spent a few years as an Anglican lay missionary in West Africa before emigrating in 1835 to New Zealand. Between 1839 and 1842 he helped Rev. Robert Maunsell (1810-1894) establish a mission station at Maraetai, Waikato Heads. Graduating from these duties, Ashwell set up and ran a mission station in the Waikato (1843 to 1863). Ashwell did not forget his missionary colleague though and remained in contact with him, mentioning him often in his letters to Grey.

The mission station Ashwell ran was located a short distance from the rear of the pā at Kaitotehe. The pā had been built at the foot of the sacred mountain, Mount Taupiri, by King Pōtatau Te Wherowhero (?-1860), paramount chief of the Waikato tribes. Kaitotehe lay on the flat and fertile land of the west bank of the Waikato River, opposite the settlement of Taupiri and within close vicinity of Ngāruawāhia. From this location, Ashwell was responsible for a large district of around 70 miles, comprising thirty villages and extending as far as Port Russell. Despite not having very robust health, Ashwell’s already busy working life was also occupied with running the mission station’s school for Māori children. Under his direction and indefatigable energy, the school grew and developed. From a colonial perspective it was successful (up until the war in the Waikato), leading Cowan to describe it as the “centre of religion and secular learning on the mid-Waikato” (1934: 21).

Ordained by Bishop George Augustus Selwyn, Ashwell is described as being temperamental and eccentric. Despite this he was influential and respected by the Waikato Māori, who called him Te Ahiwera or Hot Fire. He was not, however, supportive of the growing Kīngitanga (King) movement in the area and his letters are full of references to the growing unrest. When war broke out in the Waikato in 1863, he evacuated to Auckland. Based at Trinity Church in Devonport from 1866, he ran the Parish of the Holy Trinity, which at the time incorporated all of the North Shore. Whilst in this role, he also continued working as a missionary with Māori, holding a “Maori Service once a month at the Lake” (located between the suburbs of Takapuna and Milford), as well as working with communities in North Mahurangi and Te Muri (1871, GLNZ A13.10). After working again in the Waikato during the 1870s, he permanently returned to Auckland. He retired in 1883, ending a missionary career of over 49 years.

The mission station at Kaitotehe was much drawn, painted and later photographed, including by the painter George French Angus (see above) and photographer Bruno L. Hamel (see further on). The latter visited the area in 1859, as part of the Government Scientific Exploring Expedition conducted by Dr. Ferdinand Hochstetter (see photographs further on). In addition to impressions showing the whole mission station, artists and photographers also focused on capturing specific elements. This included not only the school but also the church, which combined both Māori and Gothic Revival architectural elements, as seen in the sketch below. Hochstetter described the church as “a pretty specimen of a Maori building” and noted “its door-posts and gable-beams [were] gayly painted” (1867: 308).

Schooling at the mission was conducted in a "highly finished and ornamental weatherboarded house" containing a central school room, dining room and dormitory (New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian, 14 September 1853). It is this mission school, that was the subject of many of Ashwell’s letters to Grey during the 1850s. Although Grey does not appear to have visited the school until January 1863, as the war in the Waikato was beginning to ignite, he was, however, pivotal in establishing and setting the tone for Māori education policies during the 19th century and well into the next. Grey believed in colonial theories of ‘civilisation’ and racial amalgamation (retaining and combining the most desirable aspects of European and Māori culture), although the affect was more akin to assimilation (ensuring Māori learnt European ways). Central to achieving these goals was his approach to education policy and for this he consulted with Rev. Maunsell, who was considered an authority on Māori education. Accordingly, when first in office Grey established the Education Ordinance 1847 to support Anglican, Roman Catholic and Wesleyan mission schools throughout New Zealand with public funds. This policy was founded on instruction in religion, the English language and training in manual and domestic skills, and was officiated by government inspectors. The later Native Schools Act 1858, which provided subsidies for ‘native’ mission boarding schools, was also based on these principles but additionally required Māori children to board on site.

Ashwell references Grey’s involvement in education policy when he wrote to him in 1852, stating "[k]nowing the interest which you take in the formation of Schools for the instruction of the Aborigines I take the liberty of bringing under your notice the present position and prospects of the School at Kaitotehe" (25 November 1852, GLNZ A13.4). Over the years of their correspondence, Ashwell informed Grey about the growing numbers of pupils at Kaitotehe. This was perhaps as a less informal way of reporting on the mission school’s progress, although Ashwell was also an officially licensed inspector. For example, in 1850 Ashwell states that the number of pupils had risen to around 30-40 (24 May 1850, GLNZ A13.2). Less than two years later, he is pleased to report the number of pupils had nearly doubled to “sixty[,] chiefly girls" (27 December 1852, GLNZ A13.5). By the time Hochstetter visited in 1859, it had risen again to 94 pupils, consisting of 46 girls and 48 boys (1867: 307-308).

Although Ashwell does not describe the daily routines of school life in his letters to Grey, he does elaborate on this in Recollections of a Waikato Missionary:

“The rules were as follows:-- An hour before breakfast--6 a.m. in summer, 7 a.m. in winter--the bell rang: prayers and Bible-class for an hour; this I always took. 8 a.m. in summer, and 9 a.m. in winter, the bell rang for breakfast. 9 a.m. in summer, and 10 a.m. in winter, the bell rang for school. 1 p.m., dinner. 2 p.m., the sewing-school for girls, and farm work for boys, till 5 p.m. At 6 p.m., tea. After tea, the elder girls were engaged knitting, and the others in a reading class. Our usual course of instruction was reading, in native and English grammar, geography, history, writing, arithmetic, and singing …” (Ashwell, 1878: 20).

As the rules outline, there was a close adherence to the Education Ordinance fund regulations. This included foci on literacy and religious studies, as well as gendered activities for the pupils (as was typical of the time); namely indoor household work for the girls and outdoor farming for the boys. The latter is also revealed by Hochstetter’s description of the school during his visit. He observed that “Maori girls, who are here instructed in different branches of domestic work, while the boys are trained for agriculture and all sorts of useful trades” (Hochstetter, 1867: 309).

Despite Grey's departure from New Zealand in late 1853, to take on the post of governor of Cape Colony (South Africa), Ashwell continued to advise him about schooling in the Waikato and ask for assistance. In 1855, for example, he writes:

"I feel assured that your Excellency still feels an interest in the progress of Education amongst the Aborigenes [sic] of New Zealand. The Waikato Schools I believe are still progressing. Mr Maunsell Number 80 Scholars Mr Morgans 30 Half Castes & Native and Taupiri 52". (GLNZ A13.8, 1 September 1855).

"We have maintained, an average number of 50 Boarders, during the last three years and for their support have received only £100 per annum, from Government Grant, besides these scholars we board and pay an English Female Assistant. We are now more than £300 in debt. The question has now been forced on my attention whether I should not considerably diminish the number of scholars. This step I should deeply regret …" (ibid.).

Grey responded to Ashwell's request for assistance by sending him £100 towards the costs (27 December 1852, GLNZ A13.5). As this and other letters show, Grey played an important role in supplementing the school’s funding.

Something which we can identify with today, is the cost of food. Ashwell advised Grey in 1852 that he feared "food rising in price in consequence of the late discovery of gold in this Hemisphere" (24 November 1852, GLNZ A13.4). This comment is probably in reference to Charles Ring’s discovery of a small amount of gold near Coromandel town in 1852. As a solution, Ashwell informed Grey that he had bought around 100 acres of land, located 2 miles away, with the intention of enabling the mission station to be self-sufficient. In outlining his plans, he strategically appealed to Grey to help finance this endeavour:

"Revd. R Maunsell has undertaken that his school should plough and harrow it for us. For his preliminary operation, we need between £30 & 50, and my object now is to solicit this assistance from your Excellency. I forbear enlarging on the advantages which I expect to result to us from this undertaking. I am aware that your Excellency has more than once expressed strong opinions, upon the desirableness of helping Institutions to gain their own support, and I indulge strong hopes that the economical way in which the aid hitherto gained to us has been expended will induce your Excellency if possible to grant us the aid so much needed, at this juncture" (24 November 1852, GLNZ A13.4).

This tone and approach reappear in subsequent correspondence, where Ashwell states "[t]he kind interest your Excellency takes in our institutions is an encouragement to persevere" (27 December 1852, GLNZ A13.5). Even after Grey had left for South Africa, Ashwell continued to seek personal funding from him, and he was evidently successful. In his letter of 1855, he thanks Grey, stating "[t]he benefit Taupiri Institution has received from your present of Plough and Horses, induces me again to thank you for your many kind favours which have greatly encouraged us in our work. We trust that Agricultural Labours will eventually render the Institution self supporting" (GLNZ A13.8, 1 September 1855).

Evidently the strain of debt wore Ashwell down, as did reports by Rev. Maunsell about the school’s financial situation. In his letter of 28 March 1853, Ashwell took great pains to explain the reasons for the debt to Grey. He also enclosed accounts to back up his statement, which included a stated annual cost of £4.5.0 per child:

"I have the honor [sic] of forwarding for your inspection an account of the Funds of the Taupiri Institution from which your Excellency will see that the amount of the Debt was £321.0.0 at the time you so kindly sent the £100. Probably a mistake arose through a letter published in the New Zealander by the Revd. R Maunsell in October last he only knew that the School was considerably in debt, which being sufficient for the object of his letter he never enquired the amount. The annexed account was given to the Inspector in October last. it will be seen that the outlay in a suitable Building is the cause of the debt being so heavy. Your Excellency will be pleased to hear that this the blessing of God our School continues to prosper and still affords us much satisfaction" (28 March 1853, GLNZ A13.6).

|

| Excerpts of accounts enclosed with a letter by Rev. Benjamin Ashwell to Sir George Grey. 28 March 1853. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, GLNZ A13.6. |

|

| Excerpts of accounts enclosed with a letter by Rev. Benjamin Ashwell to Sir George Grey. 28 March 1853. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, GLNZ A13.6. |

|

| Excerpts of accounts enclosed with a letter by Rev. Benjamin Ashwell to Sir George Grey. 28 March 1853. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, GLNZ A13.6. |

A more formal report about the school, including its finances, appeared in the Supplement to the New Zealand Herald on 11 June 1853. This report was written by Ashwell and formed part of a series of official ‘Accounts of the Schools in the District of Auckland’ in the supplement. Without any apparent concern for modesty, Ashwell ended his report by stating “[th]e personal and painstaking labours of the Rev. Mr. Ashwell and of Mrs. Ashwell, in teaching the children, and in the general care of the school, are most exemplary” (ibid.).

As well as discussing the school’s debts with Grey, Ashwell wrote to inform him that his departure for South Africa was still felt by Waikato iwi, even after more than a year had passed:

"The Natives of Waikato often speak of your Excellency, and do not forget the many benefits they received from your kind and judicious administration. They much regret your not returning. We also join with them in their regrets, but as there is something selfish in our wishes, our prayer to God is that it may please him to make you equally successful in your endeavours to benefit the numerous Aboriginal Tribes of Southern Africa as you were in this country" (1 September 1855, GLNZ A13.8).

These feelings are echoed by a farewell address to Grey, that was published in the Maori Messenger: Te Karere Maori at the time of his departure in late 1853:

|

| 'Farewell Address From The Scholars of Taupiri School' from the Maori Messenger: Te Karere Maori, Volume V, Issue 131, 29 December 1853, p4. |

The article also lists the female students who signed the address, one of whom is perhaps the pupil Ashwell wrote to Grey about in 1855:

"[o]ne of our School girls, who presented the address to your Excellency wishes to write to you. I gave her permission as you expressed yourself pleased with her. I enclose her letter which is entirely her own you will excuse it as such" (1 September 1855, GLNZ A13.8).

Unfortunately, this letter does not accompany Ashwell’s letter and searching using the students’ names from the newspaper article has not been fruitful. However, it may yet be waiting to be found somewhere in the library’s collections.

|

| Patrick Joseph Hogan. Taupiri Maori signing an address to Sir George Grey prior to his departure from New Zealand. 1853. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 5-785. |

The Grey New Zealand Letters contain a wealth of information about 19th century colonial life in Aotearoa New Zealand, including missionaries and missionary stations, religion, governmental policy and education. At the heart of these letters and indeed any correspondence, are the relationships between people and the way these develop, strengthen or may even rupture over time through the activity of writing. Hopefully this post has inspired you to dip into the letters available online and make your own discoveries; for this period in time remains hugely relevant to the present day, including the reclamation of Mātauranga Māori and whakapapa.

Author: Dr Natasha Barrett, Senior Curator Archives and Manuscripts

Bibliography

Letters

Newspapers

Ashwell, Rev. Benjamin (1853) 'Taupiri School'. In: New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian, Volume IX, Issue 847, 14 September 1853, p4. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZSCSG18530914.2.10 [Accessed: 16/04/2020].

Anonymous (1853) ‘Farewell Address from the Scholars of the Taupiri School’. In: Maori Messenger: Te Karere Maori, Volume V, Issue 131, 29 December 1853, p4. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MMTKM18531229.2.14 [Accessed: 16/04/2020].

Other publications

Ashwell, Rev. Benjamin (1878) Recollections of a Waikato Missionary. Auckland: William Atkin, Church Printer. Available at:

http://www.enzb.auckland.ac.nz/document/?wid=4636&page=1&action=null [Accessed on: 17/04/2020]. N.B. The letters in this publication were originally published in the New Zealand Herald and then re-printed in the Auckland Church Gazette (1874-1876).

Cowan, James (1934) ‘Famous New Zealanders: No. 18: The Rev. B. Y. Ashwell: Missionary of Waikato: The Story of a Peacemaker’. In: The New Zealand Railways Magazine. Volume 9, Issue 6, 1 September, pp17-22. Available at: http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Gov09_06Rail-t1-body-d7.html [Accessed 20/04/2020].

von Hochstetter, Dr Ferdinand (1867) New Zealand Its Physical Geography, Geology and Natural History with Special References to the Results of Government Expeditions in the Provinces of Auckland and Nelson. Stuttgart: J. G.Cotta. Also digitised by the University of Auckland

[Accessed 18/04/2020].

Lineham, Peter (n.d.) The Development of Churches on the North Shore, Auckland. Available at: http://www.methodist.org.nz/files/docs/wesley%20historical/northshorereligionrev6a.pdf [Accessed: 17/04/2020].

Tagg, M. A. and Aswhell, Rev. Benjamin Y. (2003) Te Ahiwera - A Man of Faith: The Life of Benjamin Y. Ashwell, Missionary to the Waikato. Together with his Recollections of a Waikato Missionary. Auckland: Anglican Historical Society.

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.