"I never thought freedom would come down to this."

“Those entering the sex industry as workers do so primarily for economic reasons, a factor highlighting the economic marginalisation of some sectors of our communities, and the difficulties of securing well-paid employment.” - Jan Jordan, 2005.

On the 25th of June 2003, parliament passed the Prostitution Reform Act on a conscience vote, and Aotearoa New Zealand became the first country in the world to decriminalise sex work. The Act’s slim margin of success (60-59) reflected the controversial nature of the legislation at this crucial tipping point. While this was a progressive step, the road to decriminalisation was littered with societal angst. Until this point, the morality, contractual legitimacy, and humanity of sex work was often narrated by a hostile and conservative media climate. The law consistently undermined the profession, and sex workers were frequently either demonised or subject to paternalistic saviour complexes. Outside public debate, the lived experiences and reality of sex workers did not follow these popularised stereotypes.

As a branch of the service industry, sex workers satisfy a demand in society, and capitalise on it by selling their labour. When stripped back to its core – contract law – this is no different to other service roles such as making coffees, helping someone exercise, or providing therapeutic massages. As a result, stigma often stems from (external) social forces, and does not accurately account for the experiences of the workers themselves. My research aims to approach sex workers and their history on their terms, with respect for the profession and the people in it.

Despite being one of Aotearoa’s earliest industries and turning over hundreds of millions in revenue each year, the sex economy is less comprehensively researched than other sectors. My work across the following articles examines the economics of the industry as Aotearoa underwent economic restructuring, focusing on the workers themselves, from 1984 to 2003. This two-decade period begins with the election of the Fourth Labour Government and ends with the decriminalisation of sex work. This is a story of marginalised yet determined identities – queer men, cisgender women, and transgender women – taking advantage of commercial sex to carve out economic freedom and independence for themselves in a rapidly evolving Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. As the first of five articles, the following sections cover a brief history of sex work in Aotearoa, the fight for decriminalisation, some reasons why workers entered the industry, and some evolving perspectives on sex work in the 1980s and 1990s.

Sex work: a heritage site

Aotearoa has a history of policing sex workers that stretches back to the arrival of the British. The profession as we know it today is a European import, and in the early days of colonial Aotearoa, sex was traded frequently throughout the country’s ports, including Tāmaki Makaurau. Moral concern over the practice fuelled anxieties around ‘lawlessness’, and it is likely that this concern played into decisions related to the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Far more men than women migrated to Aotearoa, particularly during the gold rush in the 1860s. This gender imbalance created more demand for sex workers. The industry was central to Aotearoa’s economy – particularly in Kororāreka (Russell) – but its growth led to concerns around women immigrating for sex work instead of low-paid domestic service. This contributed to the passing of the Contagious Diseases Act 1869, which required female sex workers to register with the police and undergo compulsory physical examinations for venereal disease. These examinations were invasive and entrenched stigmas around immorality and ‘dirtiness’. Sex workers were also often arrested on various charges, such as vagrancy, but their profession was not yet illegal. This changed with the Police Offences Act in 1884, which criminalised public soliciting from “common prostitutes”. Both statutes were controversial, with some women’s groups criticising the targeted punishment of sex workers against the freedom awarded to their male clients. This legal framework – punishing the worker while allowing the client to walk free – lasted in different forms until decriminalisation in 2003.

|

| Image: Dame Catherine Healy, NZPC [New Zealand Prostitutes Collective] Auckland. |

Despite legal controls, the industry persisted through the turn of the twentieth century. Numbers are difficult to gauge, but research suggests up to 10 percent of women used sex work to support themselves at this time. Many engaged in house-sharing arrangements, taking turns to work and care for each other’s children. In Tāmaki Makaurau, the establishment of Myers Park and its kindergarten benefitted sex workers, alleviating some of the pressures of childcare. By 1938, the First Labour Government had created Aotearoa’s social welfare system, which somewhat reduced the supply of workers in the sex industry. This is because while sex worker numbers tend to increase during market recessions, a solid state support system softens the impact of a depressed economy. In this way, sex work is directly linked to the economy at large – a thriving stock market means good business for workers. It also helps explain why the shift away from a welfare state in the 1980s increased worker numbers in the sex industry.

The post-war era enjoyed a long economic boom that kept numbers down, with Kiwi women slower to capitalise on industrial potential than their international contemporaries. Nonetheless, further controls were passed. The Crimes Act 1961 criminalised soliciting, brothel-keeping, and “living off the earnings of a prostitute”. This was followed by the Massage Parlours Act 1978, which strictly regulated the operation of parlours due to their ‘wink-wink’ status as fronts for sex work. These more recent laws were unevenly enforced, with Māori and transgender workers charged at far higher rates than Pākehā. Amendments to the Crimes Act in 1981 also criminalised soliciting for men, impacting the queer street trade as well as transgender workers, who were often misgendered and prosecuted under this law. In the late 1980s, parliament also considered criminalising escort agencies, but ultimately policed these newer businesses by controlling sex advertising.

This is the legal setting that reigned until the twenty-first century, with the people in this story experiencing it as part of their daily lives. But in 1987, the New Zealand Sex Workers’ Collective (NZPC) entered the scene, pushing for a legal revolution in the form of decriminalisation.

|

| Image: The sex industry was a topic of public debate in the 1990s. This cartoon was presumably in response to Auckland Council's attempts to restrict the industry. Listener 1996, NZPC, Auckland. |

The Prostitution Reform Act 2003

The laws that governed sex work in the 1980s and 1990s created a complicated grey area for workers. It was illegal for them to offer sex for money, but not for a client to offer money for sex. As a result, a subtle dance arose around contractual negotiations, one that police often exploited. Discussing “extras” could be tense, with any mistakes on the part of the worker potentially resulting in their entrapment, a soliciting conviction, and a ten-year ban on working in a parlour. According to the Ministry of Women’s Affairs in 1992, this legal framework could trap women in the sex industry by limiting their ability to move into other professions. The laws also prevented workers from getting a mortgage, or travel visas, and interfered with child custody battles. Finally, anti-procurement clauses designed to prevent pimping also criminalised women who used commercial sex to support their partners and children.

On a broader scale, the laws were regressive and dysfunctional. They continued the legal tradition of punishing the (predominantly female) workers while ignoring the (male) clients. In this quasi-legal space, it was challenging for the NZPC to educate workers on safe sex amid the Aids epidemic. Where commercial sex was occurring illicitly, proprietors were loath to display safe sex information, given the risk of a brothel-keeping charge.

As a result, the prime focus of the NZPC became a lobbying effort to push for a decriminalised sex industry. Several members of parliament in the Fourth National Government supported this from the early 1990s, although it was continually de-prioritised. Eventually, it disappeared from the National Party’s agenda, but was picked up and passed under a Labour Government in 2003. Both the NZPC and parliamentarians favoured decriminalisation over legalisation throughout the lobbying process. The latter – as practiced under Victorian state law in Australia – had resulted in the monopolisation of the industry, with a small number of men trading brothels for millions. Fearing this would spread to Aotearoa, the NZPC sought to prevent a legalised model, arguing that decriminalisation would better support workers and small businesses. The Prostitution Reform Act 2003 enacted this, repealing all laws that functioned against sex workers (but kept the anti-procurement sections).

As succinctly pointed out by Jan Jordan in 1998, decriminalisation was only the first step. The focus afterwards needed to turn to economic reforms that would reduce the need for women to turn to sex work for freedom and independence. A quarter-century later, the central motivator for entering the industry remains economic.

While sex work is driven by economics, the majority of workers make a conscious choice to engage with the industry. Reporting from the 1980s and 1990s tended to be paternalistic or condescending, assuming workers lacked agency or were somehow immoral. While the context of the 1980s-1990s was very different, these perspectives were still damaging. The majority of workers are deliberate with their choices, despite in some cases having no viable alternative. The motivation behind “for the money” can also be understood differently by different workers. For some, it means childcare and flexibility, for others, university tuition fees and student loans, even financial goals like a deposit for a home. Many workers – particularly women – also cite the community and camaraderie between workers as an important source of connection and safety. This was particularly strong for transgender workers of colour, who often had little choice but to trade on the street. Several of these women highlight the strong chosen whānau links established there, including anecdotes of the same doctor in Ponsonby who helped facilitate their transitions. While discrimination against transgender women has eased over time, the economic pressures that make sex work attractive for these demographics remain. Workers largely still enter the industry for the same economic reasons. In this sense, sex workers to this day represent many of the inequalities in Aotearoa society.

|

| Image: New Zealand Herald. NZPC Auckland. |

Shifting perspectives

The ways sex workers viewed themselves were diverse, but a common thread in the 1980s-1990s compared commercial sex to a reductionist interpretation of office work and marriage. This theory argued that being a female office worker or a housewife made one more subservient to men than sex work. Jan Jordan argued commercial sex was very similar to “straight” work (employment outside sex work), and argued it could be compared to traditional marriage structures because both were a bargain on sexuality. This view was relatively common in the archives, with Rainton Hastie (one of the architects of the Tāmaki Makaurau sex industry) agreeing that marriage was just as transactional as sex work. One article proposed that if all women charged men for every sexual encounter, women would have the financial power. Another referred to the job as “do it yourself socialism.” In this view, sex workers are entrepreneurs, and capitalise on male demand for their benefit.

This entrepreneurial framing links to another dominant view on commercial sex in the 1990s, which is as a capitalistic venture. True to vanguard neoliberal principles, the politicians who supported decriminalisation all framed the sex industry as a private enterprise that the state should have no role in restricting. In the words of National Member of Parliament Katherine O’Regan, “If you've got a willing buyer and a willing seller...what right has the state to interfere?” Others agreed – academic Jody Hanson proposed that the country should take advantage of the industry, marketing Aotearoa to tourists as a sex destination (similar to Amsterdam). The estimated annual contribution of $15 million to the economy did not materialise – Hanson was rather swiftly dismissed because her suggestion clashed with New Zealand Tourism’s ‘clean and green’ image. In 1993, Inland Revenue also began to take notice, meeting with the NZPC to discuss taxing sex workers. Their approach was relatively neutral on the legality of the industry, with a statement from 1999 reading, “Our organisation pursues the business dollar irrespective of the source of the business activity.” After some initial resistance, workers slowly began to pay their taxes (and GST, if their income breached $30,000 per year). In return, this paper trail gave workers greater access to societal institutions, including banks and eligibility for mortgages.

In some ways, this ‘purely business’ approach was consistent with how sex workers already viewed their profession. To many, the job was just a job, a variant of contract law that was no different to working a 9-5. Workers used various strategies to maintain separate spheres of work and private life (particularly those with partners), such as avoiding excessive intimacy with clients by enforcing a strict no-kissing rule. This compartmentalised approach to work-life balance was summarised by a worker in 1994, who wrote that sex work is the sale of a service, not a person, and argued they maintained their agency at all times. A sex worker’s relationship with their job ranged from satisfied to apathetic, and their work identity evolved based on their individual experiences and personal degree of success. Naturally, this reflects the experiences of many of us when asked about our jobs, and highlights the similarities between selling one’s productivity to a company and selling an intimate experience to a client. Understood in these terms, sex work aligns with “straight” work in many areas.

In broad strokes, sex workers can be understood as a diverse group of economically marginalised people who have used the industry to carve out their freedom and independence. The similarities to “straight” workers far outweigh the differences, with the sex industry standing as a microcosm for wider society. This era in particular – the 1980s and 1990s – is important due to the significant economic restructuring occurring throughout Aotearoa, and much can be learned about these changes from the experiences of sex workers. My next article will zoom in on the people and places that were important to the industry, as well as the crucial role played by Auckland Council.

|

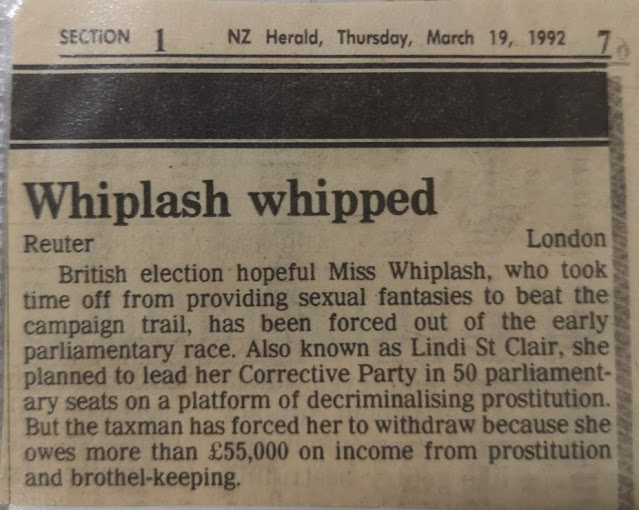

| Image: 'Whiplash whipped.' New Zealand Herald, 1993. NZPC Auckland. |

Author: Henry Grey

Henry was a 2023 Summer Scholar with the Auckland History Initiative (AHI), a research collaboration at the University of Auckland. The AHI views Summer Research Scholarships as an integral way to engage students in Auckland history and to strengthen relationships with the Auckland GLAMR (galleries, libraries, archives, museums and records) sector. These students spend 12 weeks over the summer break researching in the varied and rich archives around Auckland under the supervision of Professor Linda Bryder and Dr Jessica Parr.

Henry (he/him) is currently studying toward a Bachelor of Laws at the University of Auckland, but the bulk of his tertiary studies thus far have been under a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and History. A perpetual debater, he was attracted to these disciplines because they offered an opportunity to explore the contentious and thorny issues of our time. The focus of Henry's research was the economics of sex work, beginning with the neoliberal reforms in 1984, and ending with the Prostitution Reform Act 2003, which decriminalised the industry. Flowing from an aim to investigate the impact of neoliberalism in less obvious, non-unionised spaces, his work covers the ways that the sex industry mirrored and interacted with wider Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. In particular, Henry's research zooms in on the diversity of the workers themselves - who they were, why they entered the industry, and how they experienced the self-labelled 'Whorearchy'. These were marginalised yet determined identities - queer men, cisgender women, and transgender women - who took advantage of commercial sex to carve out economic freedom and independence for themselves in a rapidly evolving Tāmaki Makaurau.

#You can also read three other blogs written by Henry on the Auckland History Initiative website:

Part 2: People, places and power that be

Part 3: Neoliberal technologies and the chameleons who adopted them

Part 4: "We are not 'The Warehouse'"

Part 5: The Whorearchy

Bibliography

Jan Jordan, “The Sex Industry in New Zealand: A Literature Review”, Ministry of Justice, March 2005: 75.

Nicola Legat, “Money can’t buy me love”, Metro, 1988.

Contagious Diseases Act 1869 (32 and 33 Victoriae 1869 No 52), 8.

Police Offences Act 1884 (48 VICT 1884 No 24), 23.

Saana Judd, “The Contagious Diseases Act 1869: Immoral, Unequal, or Necessary?”, Auckland History Initiative, 2022.

Julie Hill, “Dark side of the rori”, North & South no. 356, November 1, 2015: 83-98.

David Burke-Kennedy, “On the Game: The Sad, True Stories of Auckland’s Prostitutes”, Metro, April 1984.

Unknown author, “Policies blamed for increase in prostitution”, Reuter, January 31, 1992.

Jennie Fulton, “Pros or Cons: sex work in Wellington 1950-1989”, Agenda, 1989.

Catherine Healy, Ahi Wi-Hongi and Chanel Hati, ‘It’s work, it’s working: The integration of sex workers and sex work in Aotearoa/New Zealand’, Women’s Studies Journal 31 (no. 2): December 2017: 50-60.

Darryl Passmore, “Ministry in campaign to revamp prostitution”, Sunday Star, March 1, 1992.

Passmore, 1992; Gita Parsot, “Street legal”, Evening Post, early January, 1993.

Jane Clifton, “Pimps won’t benefit from soliciting law – Williamson”, The Dominion, May 27, 1993.

Phil Jarrett and Roberta Perkins, “The working girl’s friend”, The Bulletin, September 13, 1988, File: “Media 89/92”, NZPC Auckland.

Stacy Gregg, “The business of pleasure”, Sunday Star Times, November 10, 1996.

Siren no. 15, New Zealand Prostitutes’ Collective, April 1998: 35.

Deborah Telford, “The oldest profession in the world”, Sunday, May 30, 1990, File: “Media 89/92”, NZPC Auckland; Pat Rosier, “Trick or treat”, Broadsheet, September 1991; Parsot, 1993; Jan Jordan in Sian Robyns, “Giving ‘working girls’ a break”, unknown publication, 1991.

Stephen Wright, “Hamilton’s sex industry”, Nexus, March 4, 1996; Rosier, 1991.

Siren no. 12, New Zealand Prostitutes’ Collective, April 1995.

Jan Jordan, Working Girls (Auckland: Penguin Books, 1991).

Lynn Grieveson, “Sex for sale”, Scope, June/July 1991.

Claire Harman, “Should it be decriminalised?”, Christchurch Press, September 10, 1996.

Paul Holmes & Norman Stanhope, Interview transcript, IZB, February 10, 1993, File: “Articles 95/96”, NZPC Auckland; Gregg, 1996; Mark Revington, “Sin city”, The Listener, November 29, 1997, File: “Newspaper Articles 97/98”, NZPC Auckland.

Neil Reid, “Taxmen hook up call girls”, Truth, November 1993, File: “Media 89/92”, NZPC Auckland.

New Zealand Police Association, “IRD gets heavy with sex trade”, unknown publication, December 12, 1999.

Paulette Crowley, “Sex for sale”, Sunday News, March 8, 1992; Siren no. 10, New Zealand Prostitutes’ Collective, April 1994.

Veronica Harrod, “Playing the oldest game of cat and mouse”, The Dominion, April 27, 1993.

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.