Resilience: The Auckland Māori Community Centre

The Māori Community Centre, set up in 1947, was an important component in the reestablishment of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei’s community identity. During a period of significant upheaval and devastation for Ngāti Whātua, the Centre provided space for a temporary Marae and supported the process of rebuilding within the hapū. In understanding the role the Māori Community Centre played for Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, it is necessary to outline the trials faced by the hapū in the early-to-mid twentieth century. In particular, the encroachment of urban sprawl onto Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei’s land set in motion a series of devastating events, cumulating in the destruction of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei’s marae.

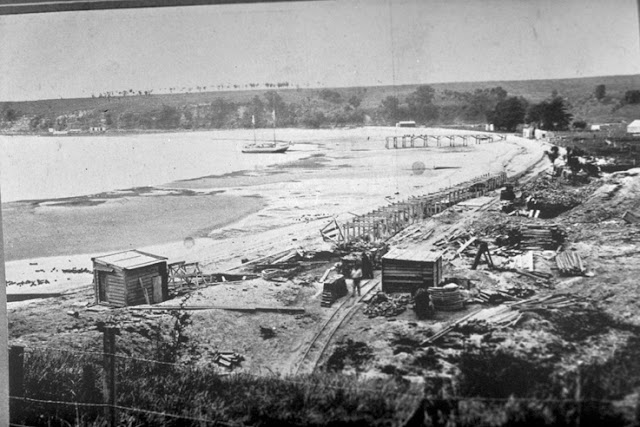

At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were two key events that negatively impacted Ngāti Whātua. In the first instance, the increasing urban population of Auckland required extensive public works to be carried out in order to install and update urban utilities. While objected to by Ngāti Whātua in 1905, the Government nonetheless passed an Act of Parliament to confiscate the land at Ōkahu Bay so a sewer pipe could be installed across the beachfront, in front of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei’s ancestral village (shown in the image above). The 1987 Waitangi Tribunal report on the Ōrākei Claim explains that this sewer pipe, completed in 1910, began a series of devastating events that impacted Ngāti Whātua. Not only did Auckland’s effluent discharge into Ōkahu Bay, contaminating Ngāti Whātua seafood beds, but the pipeline also prevented surface run-off into the ocean.

As a result, not only was Ngāti Whātua deprived of their kaimoana, but their ancestral village was swamped. Secondly, as the Waitangi Tribunal has found, the Crown desired to acquire the land for European settlement even though Ōrākei land was considered ‘not for sale’. Consequently, by 1914, the Crown had obtained 460 acres of Ngāti Whātua’s land. While many owners believed they could keep the sections their homes stood on, this was not the case. Eventually, any Ōrākei tenants who resisted had their land seized under the Public Works Act 1882.

In 1952, another devastating and traumatic act by the Crown was inflicted on Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei. In 1951, the Crown seized the last 12 ½ acres belonging to Ngāti Whātua, leaving them with just the Ōkahu cemetery, according to the 1968 publication The Maori people in the nineteen-sixties: A symposium. While the site on which the old village stood was desired by the Crown for a park, it was also on the route the Queen would take during her official visit in the summer of 1952-1953. As such, on the pretext of the village being an eyesore and potential centre for disease, an image the New Zealand Government did not want to portray to Queen Elizabeth II, combined with the Crown’s want of a park, the remaining occupants of the village were evicted – some having to be physically carried out. Upon eviction, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei’s village and marae were demolished and burnt (image below) and in July 1952, a playground was established on the site, as detailed in the Waitangi Tribunal report on the matter.

From its establishment in 1947, through to its peak in the mid-1960s, the Māori Community Centre became a central space for the regeneration of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei. During its lifetime, the Centre was administered by various Trusts. Most notably, the Community Centre was headed by a Trust Board of fifteen members composed of members nominated by the Waitematā Tribal Executive, Department of Māori Affairs, the Māori Women’s Welfare League and Rotary Clubs until 1951. By 1951, the management of the Centre was handed over to the Tribal Executive, and by 1953, this Executive took over the running of the Centre. However, under this Executive, the Māori Community Centre slowly declined in use. By the late-sixties, it was decided that the Centre was to be placed under the custodianship of the all-male Tribal Committee, the Ōrākei Marae Trust Board, who ran the Centre until 1974.

Once full control of the Community Centre was transferred to the Ōrākei Marae Trust Board, the Centre became an important component in the re-establishment of Ngāti Whātua’s marae. As the 1960s brought with it widespread interest in developing a Ngāti Whātua ‘urban marae’, this Tribal Committee instigated valuable work within the Māori Community Centre. As author of The History of Ngāti Whātua (1997) Ani Pihema explained, it was at the Māori Community Centre that the carvings that came to adorn the marae were created, being a place where “We could begin our carving project until the shell of the meeting house was completed and then we could return”. Moreover, it was under the Ōrākei Marae Trust Board that the Centre functioned as a surrogate Māori space in lieu of a marae which was still being constructed. As Ani Pihema elaborated, “the Māori Community Centre for six years provided a temporary marae for Auckland Māori needs until Ōrākei Marae was built.”

While this narrative has been one of destruction, it is also one that shows the unwavering resilience of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei. After experiencing the devastation of their ancestral village and marae at the hands of the crown, Ngāti Whātua were resolute to rebuild their marae. Instrumental in the rebuilding of not only their marae, but also community networks ravaged by the eviction process, was the Māori Community Centre. In addition to the fact that the Centre become a space that supported Ngāti Whātua’s continued resilience, under the Ōrākei Marae Trust Board, it also became a temporary cultural home in which Ngāti Whātua was able to rebuild, strengthen, and reassert their identity.

During his summer scholarship in 2019, Nicholas was fortunate enough to partake in the Mana Whenua project, supervised by Professor Linda Bryder. His project was focused upon fleshing out the social history of Auckland’s Māori Community Centre.

This research benefited greatly from the guidance and help from the Auckland Libraries staff. Nicholas would like to extend special thanks to Rob Eruera, Jane Wild, and the staff from the Sir George Grey Special Collections.

Find out more about the Auckland History Initiative.

Ministry of Justice. ‘The loss of the Orakei block', 19th September 2016. Available at https://www.waitangitribunal.govt.nz/publications-and-resources/school-resources/orakei/the-loss-of-the-orakei-block/.

Pihema, Ani., “The History of Ngāti Whātua”. Auckland, 1997.

Schwimmer, Erik, ed. The Maori people in the nineteen sixties: A symposium. London: C. Hurst; New York: Humanities P., 1968.

Waitangi Tribunal, Report of The Waitangi Tribunal on The Orakei Claim (Wai-9), Retrieved fifth of February 2019. Available at https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_68494556/ReportonOrakeiW.pdf

|

| Image: Sewer under construction, Ōkahu Bay, 1910. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 7-A362. |

At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were two key events that negatively impacted Ngāti Whātua. In the first instance, the increasing urban population of Auckland required extensive public works to be carried out in order to install and update urban utilities. While objected to by Ngāti Whātua in 1905, the Government nonetheless passed an Act of Parliament to confiscate the land at Ōkahu Bay so a sewer pipe could be installed across the beachfront, in front of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei’s ancestral village (shown in the image above). The 1987 Waitangi Tribunal report on the Ōrākei Claim explains that this sewer pipe, completed in 1910, began a series of devastating events that impacted Ngāti Whātua. Not only did Auckland’s effluent discharge into Ōkahu Bay, contaminating Ngāti Whātua seafood beds, but the pipeline also prevented surface run-off into the ocean.

As a result, not only was Ngāti Whātua deprived of their kaimoana, but their ancestral village was swamped. Secondly, as the Waitangi Tribunal has found, the Crown desired to acquire the land for European settlement even though Ōrākei land was considered ‘not for sale’. Consequently, by 1914, the Crown had obtained 460 acres of Ngāti Whātua’s land. While many owners believed they could keep the sections their homes stood on, this was not the case. Eventually, any Ōrākei tenants who resisted had their land seized under the Public Works Act 1882.

|

| Image: Ōkahu Bay, 1910. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 7-A2929. |

In 1952, another devastating and traumatic act by the Crown was inflicted on Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei. In 1951, the Crown seized the last 12 ½ acres belonging to Ngāti Whātua, leaving them with just the Ōkahu cemetery, according to the 1968 publication The Maori people in the nineteen-sixties: A symposium. While the site on which the old village stood was desired by the Crown for a park, it was also on the route the Queen would take during her official visit in the summer of 1952-1953. As such, on the pretext of the village being an eyesore and potential centre for disease, an image the New Zealand Government did not want to portray to Queen Elizabeth II, combined with the Crown’s want of a park, the remaining occupants of the village were evicted – some having to be physically carried out. Upon eviction, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei’s village and marae were demolished and burnt (image below) and in July 1952, a playground was established on the site, as detailed in the Waitangi Tribunal report on the matter.

|

| Image: New Zealand Herald, Māori Shacks Go Up in Smoke, 19 December 1951. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 7-A14286A |

From its establishment in 1947, through to its peak in the mid-1960s, the Māori Community Centre became a central space for the regeneration of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei. During its lifetime, the Centre was administered by various Trusts. Most notably, the Community Centre was headed by a Trust Board of fifteen members composed of members nominated by the Waitematā Tribal Executive, Department of Māori Affairs, the Māori Women’s Welfare League and Rotary Clubs until 1951. By 1951, the management of the Centre was handed over to the Tribal Executive, and by 1953, this Executive took over the running of the Centre. However, under this Executive, the Māori Community Centre slowly declined in use. By the late-sixties, it was decided that the Centre was to be placed under the custodianship of the all-male Tribal Committee, the Ōrākei Marae Trust Board, who ran the Centre until 1974.

Once full control of the Community Centre was transferred to the Ōrākei Marae Trust Board, the Centre became an important component in the re-establishment of Ngāti Whātua’s marae. As the 1960s brought with it widespread interest in developing a Ngāti Whātua ‘urban marae’, this Tribal Committee instigated valuable work within the Māori Community Centre. As author of The History of Ngāti Whātua (1997) Ani Pihema explained, it was at the Māori Community Centre that the carvings that came to adorn the marae were created, being a place where “We could begin our carving project until the shell of the meeting house was completed and then we could return”. Moreover, it was under the Ōrākei Marae Trust Board that the Centre functioned as a surrogate Māori space in lieu of a marae which was still being constructed. As Ani Pihema elaborated, “the Māori Community Centre for six years provided a temporary marae for Auckland Māori needs until Ōrākei Marae was built.”

While this narrative has been one of destruction, it is also one that shows the unwavering resilience of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei. After experiencing the devastation of their ancestral village and marae at the hands of the crown, Ngāti Whātua were resolute to rebuild their marae. Instrumental in the rebuilding of not only their marae, but also community networks ravaged by the eviction process, was the Māori Community Centre. In addition to the fact that the Centre become a space that supported Ngāti Whātua’s continued resilience, under the Ōrākei Marae Trust Board, it also became a temporary cultural home in which Ngāti Whātua was able to rebuild, strengthen, and reassert their identity.

Author: Nicholas Jones

Nicholas Jones (Tūhoe, Ngā Puhi) attended Trident High School in Whakatāne. He completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Auckland with a major in History and a minor in Art History, graduating in 2018. Nicolas went on to complete Honours in History, graduating with first class honours. He is now beginning Masters in Asian Studies at the University of Auckland.During his summer scholarship in 2019, Nicholas was fortunate enough to partake in the Mana Whenua project, supervised by Professor Linda Bryder. His project was focused upon fleshing out the social history of Auckland’s Māori Community Centre.

This research benefited greatly from the guidance and help from the Auckland Libraries staff. Nicholas would like to extend special thanks to Rob Eruera, Jane Wild, and the staff from the Sir George Grey Special Collections.

Find out more about the Auckland History Initiative.

Bibliography:

Kelly, C.M., “The Auckland Maori Community Centre In The Context Of Continuity And Change In Maori Society”. Bachelor of Architecture Thesis, University of Auckland, 1983.Ministry of Justice. ‘The loss of the Orakei block', 19th September 2016. Available at https://www.waitangitribunal.govt.nz/publications-and-resources/school-resources/orakei/the-loss-of-the-orakei-block/.

Pihema, Ani., “The History of Ngāti Whātua”. Auckland, 1997.

Schwimmer, Erik, ed. The Maori people in the nineteen sixties: A symposium. London: C. Hurst; New York: Humanities P., 1968.

Waitangi Tribunal, Report of The Waitangi Tribunal on The Orakei Claim (Wai-9), Retrieved fifth of February 2019. Available at https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_68494556/ReportonOrakeiW.pdf

wow, this is so interesting! I've learnt so many new things!

ReplyDelete