Lost Neighbourhoods of Central Auckland - Maps and Early Census

The heritage collections at Auckland Council Libraries offer of wealth of information on the history of our city, including an early census, and map collections that document the built and natural environment at various points in time. Each source has its own strengths, and when looked at together, a picture of Auckland’s lost neighbourhoods can be found.

1842 Map

.jpg) |

| Image: Plan of Auckland as it stands in January 1842. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 4601 |

This plan of Auckland as it stood in January 1842 provides many details of the town in its early years. Shortland Crescent (now known as Shortland Street) was the main street at this time. Among the most densely built parts of the town is the area on the southern side of Shortland Crescent where the sites stretch through to Chancery Street. The position of hotels on the map helps show the location of some of the streets we know today. The Sir George Gipps Hotel was located on High Street (marked with the letter M). The area between Shortland Crescent and Chancery Street has many buildings, and the first of several private lanes appears.

At the bottom of the Queen Street valley, the Waihorotiu Stream runs freely through to Commercial Bay. This stream would become increasingly polluted as the population of the town expanded. It was realigned to become the Ligar Canal, an open sewer that offended with its smells for many years to come.

The shoreline has been altered substantially since 1842 when Fort Street ran along the shoreline to the west of Point Britomart, the high headland which would later be cut down and used to reclaim Commercial Bay.

At this time Auckland was the capital of the young colony, a role it would retain until 1865. Up on the ridge in Princes Street are the post office, a bank, and a hotel. Princes Street is something of a dividing line - the government offices and the residences of officials are all located east of Princes Street, above the aptly named Official Bay. Where Eden Crescent runs today are the offices of the Surveyor General, Colonial Secretary and Colonial Treasurer, located close to Government House, standing in substantial grounds to the south.

Auckland Police Census

|

| Image: Census book, Police Office, Auckland 1841-1846. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections NZMS-0025 |

From this source we know that in 1842 William Bacon, then aged between 21 and 45, lived in a timber dwelling in Chancery Street. A woman of the same age (his wife) was living with him, along with a girl aged between 7 and 14 (his daughter). They belonged to the Church of England and Bacon was a retailer. Subsequent census data reveals additions to his household and changes in employment. Between the 1842 and 1843 count, the Bacons welcomed a baby girl to their family, and an adult male joined the household (possibly an employee or relative) though he had moved out by the time of the 1844 count. By the time the last census was recorded in 1846 William Bacon was working as a ginger beer brewer, supplying a key ingredient of a popular drink of the day – brandy and ginger beer, known as a stone fence.

1866 Harding and Vercoe Map and Descriptive Schedule

|

| Image: City of Auckland, New Zealand, from actual survey by J. Vercoe and E.W. Harding, 1866. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 18 |

|

| Image: Detail showing the Chancery Street area. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 18. |

The Harding and Vercoe map shows numerous small buildings in the narrow lanes that sprouted off Chancery Street in the hollow below Bank Street (now Bankside Street). The Chancery Street neighbourhood had developed into a rowdy slum which according to the New Zealand Herald rivalled ‘the filthiest den in London.’

What this map doesn’t show is the contour of the land, but other sources including photographs, provide views of the area from higher vantage points where the topography of the neighbourhood can be seen. The large buildings at the High Street end of Chancery Street (on lots 26 and 27) are the Wesleyan Chapel and the Mechanics Institute. Both of these buildings were on elevated sites well above the densely populated hollow below.

The higher surrounding land naturally drained into the Chancery Street hollow, adding to the accumulation of filth that gathered there. An inspection of Chancery Lane in 1864 found an insanitary street of ‘miserable hovels’ lacking any means of removing slops and night soil.

|

| Image: Descriptive schedule, page showing Chancery Street to Dock Street. Auckland Libraries Collections Map 18. |

1882 Hickson Map

|

| Image: Map of the city of Auckland, New Zealand 1882. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 91. |

By this stage the standpipes that appeared on the 1866 map by Harding and Vercoe had disappeared – city residents now had household water connections from the Western Springs water supply. The maps show fire bells and plugs, gas street lamps and post boxes – all far more numerous than they had been 16 years earlier when the Harding and Vercoe map was drawn.

Queen Street was now Auckland’s main street and many of the buildings below the Grey Street intersection are built from brick (coloured red on the map). Beyond Queen Street, timber is the predominant building material (coloured yellow on the map).

|

| Image: Close up view of Grey Street. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 91. |

A close up view of the Grey Street (now Greys Avenue) area, shows a waterway still running down the gully between Vincent and Grey Streets, heading underground before it reaches Cook Street. This was a tributary of the Waihorotiu Stream which ran down the Queen Street valley (shown in the 1842 map). Like the other creeks and streams that flowed through the inner city, this stream would later be piped and covered over.

On this map we see buildings lining both sides of Grey Street, most of which were houses - verandahs can be seen outlined on the fronts of many of the dwellings. A few private lanes have made an appearance in the street, providing access to houses built behind those facing the street – more lanes and little houses would follow.

This map allows us to see details of the built enviroment that are often hidden in photographs of the day. By the 1880s numerous trees had grown up in various parts of the city, including Grey Street where London plane trees were planted in the early 1870s. These trees, and the mix of tree varieties that thrived in the gully between Grey and Queen Streets, obscure the view of houses and buildings in many photographs of the era.

Photographers often took grand views of the city from high vantage points, where larger street front buildings blocked the view of the gullies below. Surviving photographs include views of city streets and smart looking buildings – attractive images that could be sold to the public. But there was no market for views down the private lanes off Grey Street where poor residents lived. Maps such as this one provide invaluable information on what was was behind the street front.

Fire Insurance Maps

|

| Image: Auckland Block No. 37A. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 9128ap |

|

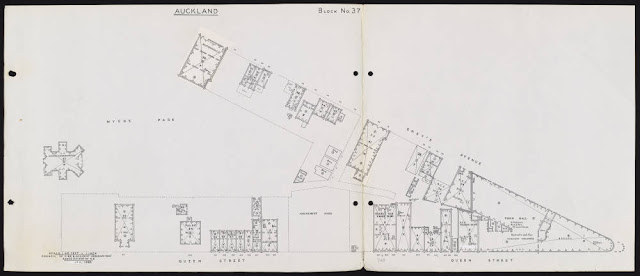

| Image: Auckland Block No. 37. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 9128an |

By the time this map was drawn in March 1929, the area between Greys Avenue and Queen Street had been transformed from an overgrown, rubbish-strewn gully into Myers Park, complete with a children’s playground and Kindergarten, clearing away 14 houses in the process.

|

| Image: Auckland Block No. 38. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 9506ap |

|

| Image: Auckland Block No. 37. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 9506an |

Though aerial photographs of the city were available by the time these maps were drawn in January 1966, the maps provide details that often can’t be seen in aerial photographs where trees and other buildings obscure the view. The 1966 map reveals significant change in this part of the Greys Avenue neighbourhood. The number of dwellings and small shops has dwindled and the area is undergoing redevelopment Auckland’s Chinatown that had been centred on lower Greys Avenue for decades was demolished, with some Chinese businesses relocating to nearby Hobson Street. The new Civic Administration building would soon open and Mayoral Drive would later punch its way through lower Greys Avenue.

These maps provide detailed information on the development of our city, and when consulted with other sources including drawings, photographs, letters, diaries, newspapers and books, we find evidence of the city neighbourhoods we have lost.

References:

Arthur S Thompson, A Statistical Account of Auckland, New Zealand, as it was observed during the year 1848, London, 1851, p.6.

Auckland Star, 19 July 1882, p.2.

Daily Southern Cross, 18 May 1866, pp.1 and 3.

Daily Southern Cross, 19 April 1871, p.3.

G W A Bush, Decently and In Order: The Centennial History of the Auckland City Council, Auckland, 1971, p.75.

James Ng, Windows on a Chinese Past, Vol. 3, p.79; G W A Bush, Decently and In Order, p.468; Graham W A Bush, Advance in Order: The Auckland City Council from Centenary to Reorganisation 1971-1989, Auckland, 1991, p.78.

New Zealand Herald, 11 April 1864, p.3.

New Zealander, 23 March 1864, p.3.

New Zealand Herald, 9 June 1866, p.6.

New Zealand Herald, 7 January 1882, p.4; 4 May 1882, p.4; 1 July 1882, p.4;

R C J Stone, From Tamaki-Makau-Rau to Auckland, Auckland, 2001, p.271.

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.