Dog taxes: a transcription tale

While our libraries are currently closed some of us in the Heritage Collections team are transcribing the GLNZ letter series from the Grey Manuscripts Collection, held in Sir George Grey Special Collections. This is a collection of letters written in English to George Grey by a variety of correspondents. Some of these were well-known public figures in the nineteenth century, while others were not.

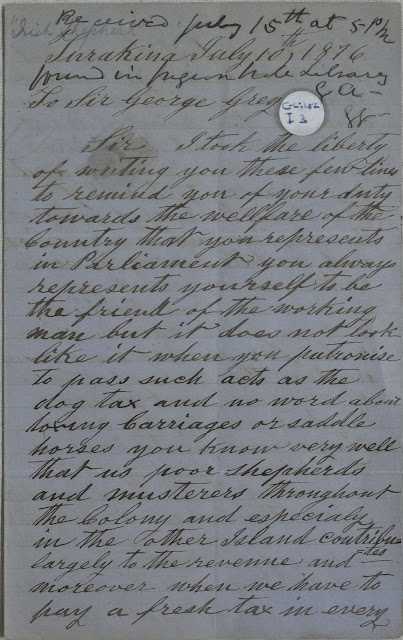

One letter that I worked on recently was a little disturbing in its tone. It begins reasonably enough:

"I took the liberty of writing you these few lines to remind you of your duty towards the welfare of the Country that you represents in Parliament"

On page two however, things take a different turn:

“I want both you and McAndrew if you value your lives and your property to vote for the Abolition and to lower the dog tax”

Signing off as "The Irish Shepherd" the writer was a musterer who was objecting to the dog tax and its dual taxation in multiple jurisdictions. This was a result of the Provincial system operating in New Zealand between 1852, when the six Provincial centres were first established, to 1876 when they were abolished by the Vogel government.

When New Zealand became a Crown Colony, separate from New South Wales in 1841, three provinces were established. They were New Ulster (the North Island, north of the Patea River in Taranaki), New Munster (the North Island, south of the Patea River and the South Island), and New Leinster (Stewart Island/Rakirua). In 1846, this was changed. New Ulster included the whole of the North Island and New Munster, all of the South Island plus Stewart Island/Rakiura. For the first time the provinces were separated from the central government. The system didn’t work as only one of the regional governments met, the other not at all. It was in 1852 that New Zealand was divided into six provinces: Auckland, New Plymouth (later Taranaki), Wellington, Nelson, Canterbury and Otago. Later provinces were set up as the populations throughout the country grew.

By the 1870s, Sir Julius Vogel believed that the provinces had broken down as they were in conflict with the Government on so many levels. He saw them as a financial liability and, except for Otago, where James Macandrew was superintendant, and Auckland, where George Grey was, everyone agreed.

Sir George denounced the abolition as a “crime against the whole human race” (Press, 22 January 1876, Page 2), while Macandrew felt that Otago would be financially ruined (Press, 14 June 1876, Page 2).

The Irish Shepherd had to contend with the differing taxes from one province to the next, and as a musterer he had to find work where he could. He also had to have a number of working dogs and to be taxed on this as well, he felt was too much.

In the Otago Daily Times Letters to the Editor, 14 June 1870 issue, a letter writer going by the pseudonym "A Farmer" takes issue with the enforcement of the Dog Tax by police: “surely it is not meant any longer to squeeze this sort of revenue out of the agricultural portion of the community who are obliged to keep dogs for cattle purposes.” He concludes, “There is some reason in charging a high tax on dogs kept within towns, where the people do so out of fancy, without need of them.”

For the same kind of reason, it was the dog tax that nearly lead to violence in the Hokianga in 1898. When Henry Menzies was put in charge of dog registrations for the council in 1897 he only received one shilling per registration as commission, maybe as a consequence of that he sent 40 summons to Pukemiro Pa. This was the village of Ngāpuhi prophet Hōne Tōia who rallied together a large group to protest against being taxed on their dogs. Many Māori owned numerous dogs for hunting and they saw themselves as being discriminated against especially when many had little involvement with the cash economy. A battle was narrowly averted by the last minute intervention of Hone Heke’s grand-nephew and MP for Northern Māori, Hōne Heke Ngapuha.

Kohukohu photographer Charlie Dawes took a series of photographs of the so-called "Dog Tax War" for newspaper publication, including of the arrival and encampment of troops:

Others show Māori surrendering weapons before their arrest and subsequent incarceration in Mt Eden Prison.

In his 1876 letter the Irish Shepherd concluded, “I am on my way to Napier looking for shepperding[sic] or mustering when the season comes for it and as sure as I am a poor Irish Shepherd I will have both you and McAndrew burnt out of your houses and your lives won’t be very safe for I got plenty of my Countrymen about Auckland and Dunedin...”

A threat indeed but you can understand the frustration. We have many books on the early days of mustering, and shepherds, early colonial and Māori life at Auckland Libraries and you can read this letter and others online at Manuscripts online.

One letter that I worked on recently was a little disturbing in its tone. It begins reasonably enough:

"I took the liberty of writing you these few lines to remind you of your duty towards the welfare of the Country that you represents in Parliament"

|

| Image: The Irish Shepherd, pseud. Letter to Sir George Grey, page 1. 10 July 1876. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, GLNZ I3. |

On page two however, things take a different turn:

“I want both you and McAndrew if you value your lives and your property to vote for the Abolition and to lower the dog tax”

|

| Image: The Irish Shepherd, pseud. Letter to Sir George Grey, page 2. 10 July 1876. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, GLNZ I3. |

Signing off as "The Irish Shepherd" the writer was a musterer who was objecting to the dog tax and its dual taxation in multiple jurisdictions. This was a result of the Provincial system operating in New Zealand between 1852, when the six Provincial centres were first established, to 1876 when they were abolished by the Vogel government.

When New Zealand became a Crown Colony, separate from New South Wales in 1841, three provinces were established. They were New Ulster (the North Island, north of the Patea River in Taranaki), New Munster (the North Island, south of the Patea River and the South Island), and New Leinster (Stewart Island/Rakirua). In 1846, this was changed. New Ulster included the whole of the North Island and New Munster, all of the South Island plus Stewart Island/Rakiura. For the first time the provinces were separated from the central government. The system didn’t work as only one of the regional governments met, the other not at all. It was in 1852 that New Zealand was divided into six provinces: Auckland, New Plymouth (later Taranaki), Wellington, Nelson, Canterbury and Otago. Later provinces were set up as the populations throughout the country grew.

By the 1870s, Sir Julius Vogel believed that the provinces had broken down as they were in conflict with the Government on so many levels. He saw them as a financial liability and, except for Otago, where James Macandrew was superintendant, and Auckland, where George Grey was, everyone agreed.

|

| Handcoloured portrait of James Macandrew. 1860s. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 503-1. |

Sir George denounced the abolition as a “crime against the whole human race” (Press, 22 January 1876, Page 2), while Macandrew felt that Otago would be financially ruined (Press, 14 June 1876, Page 2).

The Irish Shepherd had to contend with the differing taxes from one province to the next, and as a musterer he had to find work where he could. He also had to have a number of working dogs and to be taxed on this as well, he felt was too much.

In the Otago Daily Times Letters to the Editor, 14 June 1870 issue, a letter writer going by the pseudonym "A Farmer" takes issue with the enforcement of the Dog Tax by police: “surely it is not meant any longer to squeeze this sort of revenue out of the agricultural portion of the community who are obliged to keep dogs for cattle purposes.” He concludes, “There is some reason in charging a high tax on dogs kept within towns, where the people do so out of fancy, without need of them.”

Kohukohu photographer Charlie Dawes took a series of photographs of the so-called "Dog Tax War" for newspaper publication, including of the arrival and encampment of troops:

|

| Charles Peet Dawes. Soldiers in Rawene, 1898. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 1572-1378. |

|

| Charles Peet Dawes. Soldiers in defensive formation at the temporary military camp at Rawene school. 1898. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 1572-429. |

Others show Māori surrendering weapons before their arrest and subsequent incarceration in Mt Eden Prison.

|

| Charles Peet Dawes. Surrendering rifles at Waima. 1898. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 1572-357. |

|

| Charles Peet Dawes. Arrested leaders: Romana Te Paehangi, Hone Mete, Hōne Tōia (standing), Wiremu Te Makara, and Rakene Pehi. 1898. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 1572-425. |

In his 1876 letter the Irish Shepherd concluded, “I am on my way to Napier looking for shepperding[sic] or mustering when the season comes for it and as sure as I am a poor Irish Shepherd I will have both you and McAndrew burnt out of your houses and your lives won’t be very safe for I got plenty of my Countrymen about Auckland and Dunedin...”

|

| Image: The Irish Shepherd, pseud. Letter to Sir George Grey, page 3. 10 July 1876. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, GLNZ I3. |

A threat indeed but you can understand the frustration. We have many books on the early days of mustering, and shepherds, early colonial and Māori life at Auckland Libraries and you can read this letter and others online at Manuscripts online.

Author: Bridget Simpson, Heritage Collections

Further reading

Te Ara: Colonial and Provincial Government.

NZ History: 'Dog Tax War'.

Te Karere: Dog-tax rebellion centrepiece of new exhibition

Heritage et AL: Charlie Dawes: Everybody’s artist photographer

Te Karere: Dog-tax rebellion centrepiece of new exhibition

Heritage et AL: Charlie Dawes: Everybody’s artist photographer

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.