“Don’t kiss”: advice on how to dodge the ‘flu in 1918

The influenza pandemic which struck New Zealand at the end of 1918 was the most fatal disease outbreak of our country’s history. Between October and December of that year around 9000 people died, out of a total population just over one million, and smaller outbreaks reoccurred over the following years.

Browsing the pages of heritage newspapers gives an insight into how New Zealanders at that time were thinking and feeling: the advice they were given, the remedies they tried, and how they kept themselves entertained in a period of emergency comparable in some ways to our own.

Plenty of advice was published for readers on how to keep themselves healthy. The Mataura Ensign published a helpful list of “’flu don’ts” for avoiding influenza, number one being “don’t kiss.”

The writer also recommended wearing a “gas mask,” or at least “some protection over the nose and mouth.” A photo in the Auckland Weekly News from a few months later shows an ANZAC solider being welcomed home by masked women in Sydney, where mask-wearing was compulsory.

Free Lance reported that Australian women wore their masks in the most “fashionable” way, hidden beneath long veils drawn across their faces, which could have been emulated by some New Zealand readers!

As well as wearing masks, people were also advised to pay close attention to their personal hygiene, and to gargle frequently. “Don't be careless about your mouth and teeth,” one article in the Colonist reminded readers, “If you must breathe directly over the tonsils, keep them clean, and see that you breathe past clean teeth.”

Advertisements and recipes for preventatives and cures proliferated: tonics and pills to swallow, mixtures to gargle, and vapours to breathe were touted in every paper – some of which sound particularly unappetising and even alarming. One suggestion for a homemade cure instructed readers to mix lime (purchased at a brickyard) with boiling water and milk, and drink half a glass three or four times a day.

There was speculation that bee stings might prevent influenza, recommendations to use tobacco, and a letter to the editor advocating a simple remedy which was likely to prove very popular: “let the patient go to bed and keep warm, avoid antipyrine and all other reducing medicines […] but let him drink a small (or large) glass of beer every few hours.” According to the writer, “there is something in the malt or hops which seems to act as a direct antidote to the influenza germ.”

“Wawn’s Wonder Wool” medicated jacket was advertised throughout the period, to be worn for the “permanent eradication of Influenza”.

Other commercially produced remedies included “Bates’ Influenza Cure,” sold in Hastings, which apparently contained “Quinine, Squills, Senegal-, Aconite, Tolu, etc.”, “Zenol Inhalant,” a fumigating vapour to breathe in once an hour, and “Hycol,” advertised as “the strongest known disinfectant,” which customers were recommended to gargle, bathe in, and also pour down their drains.

Shops selling these cures were careful to assure customers that the stores were disinfected twice a day “so that the danger of mixing with crowds should be minimised.”

Many different disinfectants were advertised for homes, businesses, schools, and other buildings. An ad for “Spraolite” claimed that “during the fearful epidemic of last year, two rooms in one of Wellington's largest hotels were freely sprayed with Spraolite, and it is a significant fact that the occupants of those rooms were the only two who escaped influenza.”

It was generally believed that it was healthier to stay in the open air as much as possible, rather than inside warm, crowded rooms. People should be careful not to eat or drink from any “unsterilised (unboiled) and therefore possibly infected vessel […] or implement”.

In some cities, inhalation chambers were set up and free for members of the public to use as a “prophylactic measure”, but only for those not already sick.

Though never in total lockdown as we are now, people in 1918 were warned to avoid mixing in crowds and to stay at home where possible. The Mayor of Waimate advised readers of the Waimate Daily Advertiser that “country residents should only come into town when necessary,” “social visits should be avoided,” and that “business houses are requested to see that such employees as have suffered from the disease do not return to work until a certificate of health is given” – reassuring them that there would be “no charge for such medical certificate.”

The Otago District Health Officer instructed clearly: “DO NOT TRAVEL BEYOND YOUR OWN LOCALITY UNLESS ABSOLUTELY UNAVOIDABLE.” People who were found to be out and about while sick could even be prosecuted.

Public buildings were closed in many parts of the country. The official closure notices were published in the newspapers, such as that authorised by the District Health Officer of Canterbury-Westland closing the following:

Advice and injunctions to stay home were tested during the celebrations of Armistice Day at the end of the First World War. A cartoon from the New Zealand Observer shows Aucklanders gagged by the “anti-influenza precautions” and unable to voice their patriotism.

However, photographs of joyful crowds on Queen Street tell a different story:

Reading contemporary newspapers also offers a glimpse of how people kept themselves entertained while confined to home. Knitting was suggested as a “pleasant occupation for invalids” by Armstrong’s in Lyttleton, who also took the opportunity to advertise their wide range of household linens, pyjamas, and dressing gowns suitable for those convalescing (or perhaps just lounging) at home:

One advertisement suggested that “to fill in the time pleasantly and profitably we recommend everyone to lay in a stock of Magazines, Books and Papers, which can be procured at lowest prices at Alf Robinson's, Booksellers”, while another promoted a gramophone as a sure way to keep your family at home rather than risking the dangers of going out: “’The boys stay home at nights now!’ Every mother might say that – if suitable home enjoyment was provided – entertainment that would counter the attraction of outside amusement.”

Perhaps the wisest advice – equally applicable to our own time as when it was written a hundred years ago – came from Dr Joseph Frazer-Hurst, medical superintendent of Whangarei Hospital. His recommendation was to “let all the light and air you can into your houses and do not let your mind become depressed,” and suggested that the best thing to do for the time being was to simply “stay at home and grow vegetables.”

Influenza 100: Geoffrey Rice - Why do we still need to know? Part One

Influenza 100: Geoffrey Rice - Why do we still need to know? Part Two

Influenza 100: Sue Berman - The lived experience; remembering 1918-1920

Influenza 100: Jason Reeve - NZ Victims

Browsing the pages of heritage newspapers gives an insight into how New Zealanders at that time were thinking and feeling: the advice they were given, the remedies they tried, and how they kept themselves entertained in a period of emergency comparable in some ways to our own.

Plenty of advice was published for readers on how to keep themselves healthy. The Mataura Ensign published a helpful list of “’flu don’ts” for avoiding influenza, number one being “don’t kiss.”

|

| “How to dodge the ‘flu,” Mataura Ensign, 2 November 1918, Page 5. |

The writer also recommended wearing a “gas mask,” or at least “some protection over the nose and mouth.” A photo in the Auckland Weekly News from a few months later shows an ANZAC solider being welcomed home by masked women in Sydney, where mask-wearing was compulsory.

|

| “The influenza epidemic in Australia: an Anzac at Sydney welcomed by his masked relatives,” Auckland Weekly News, 27 February 1919. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19190227-35-2. |

Free Lance reported that Australian women wore their masks in the most “fashionable” way, hidden beneath long veils drawn across their faces, which could have been emulated by some New Zealand readers!

|

| “The fashionable way in which Sydney ladies are wearing the compulsory mask,” Free Lance, Volume XVIII, Issue 981, 29 April 1919, Page 12. |

As well as wearing masks, people were also advised to pay close attention to their personal hygiene, and to gargle frequently. “Don't be careless about your mouth and teeth,” one article in the Colonist reminded readers, “If you must breathe directly over the tonsils, keep them clean, and see that you breathe past clean teeth.”

Advertisements and recipes for preventatives and cures proliferated: tonics and pills to swallow, mixtures to gargle, and vapours to breathe were touted in every paper – some of which sound particularly unappetising and even alarming. One suggestion for a homemade cure instructed readers to mix lime (purchased at a brickyard) with boiling water and milk, and drink half a glass three or four times a day.

There was speculation that bee stings might prevent influenza, recommendations to use tobacco, and a letter to the editor advocating a simple remedy which was likely to prove very popular: “let the patient go to bed and keep warm, avoid antipyrine and all other reducing medicines […] but let him drink a small (or large) glass of beer every few hours.” According to the writer, “there is something in the malt or hops which seems to act as a direct antidote to the influenza germ.”

“Wawn’s Wonder Wool” medicated jacket was advertised throughout the period, to be worn for the “permanent eradication of Influenza”.

|

| “Page 4 Advertisements Column 2,” Sun, 12 June 1920, page 4. |

Other commercially produced remedies included “Bates’ Influenza Cure,” sold in Hastings, which apparently contained “Quinine, Squills, Senegal-, Aconite, Tolu, etc.”, “Zenol Inhalant,” a fumigating vapour to breathe in once an hour, and “Hycol,” advertised as “the strongest known disinfectant,” which customers were recommended to gargle, bathe in, and also pour down their drains.

|

| Advertisement for Zenol, Taranaki Herald, 14 November 1918, page 4. |

Shops selling these cures were careful to assure customers that the stores were disinfected twice a day “so that the danger of mixing with crowds should be minimised.”

Many different disinfectants were advertised for homes, businesses, schools, and other buildings. An ad for “Spraolite” claimed that “during the fearful epidemic of last year, two rooms in one of Wellington's largest hotels were freely sprayed with Spraolite, and it is a significant fact that the occupants of those rooms were the only two who escaped influenza.”

|

| Advertisement for Spraolite, New Zealand Times, 20 February 1920, Page 9. |

It was generally believed that it was healthier to stay in the open air as much as possible, rather than inside warm, crowded rooms. People should be careful not to eat or drink from any “unsterilised (unboiled) and therefore possibly infected vessel […] or implement”.

In some cities, inhalation chambers were set up and free for members of the public to use as a “prophylactic measure”, but only for those not already sick.

Though never in total lockdown as we are now, people in 1918 were warned to avoid mixing in crowds and to stay at home where possible. The Mayor of Waimate advised readers of the Waimate Daily Advertiser that “country residents should only come into town when necessary,” “social visits should be avoided,” and that “business houses are requested to see that such employees as have suffered from the disease do not return to work until a certificate of health is given” – reassuring them that there would be “no charge for such medical certificate.”

The Otago District Health Officer instructed clearly: “DO NOT TRAVEL BEYOND YOUR OWN LOCALITY UNLESS ABSOLUTELY UNAVOIDABLE.” People who were found to be out and about while sick could even be prosecuted.

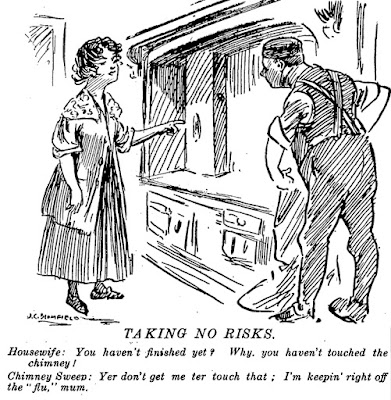

|

| Cartoon. Observer, 16 November 1918, Page 16. |

Public buildings were closed in many parts of the country. The official closure notices were published in the newspapers, such as that authorised by the District Health Officer of Canterbury-Westland closing the following:

|

| Public notices. Star, 20 November 1918, page 1. |

Advice and injunctions to stay home were tested during the celebrations of Armistice Day at the end of the First World War. A cartoon from the New Zealand Observer shows Aucklanders gagged by the “anti-influenza precautions” and unable to voice their patriotism.

|

| Blomfield, J. C. “Gagged enthusiasm.” New Zealand Observer, 23 November 1918. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, 7-A14592. |

However, photographs of joyful crowds on Queen Street tell a different story:

Reading contemporary newspapers also offers a glimpse of how people kept themselves entertained while confined to home. Knitting was suggested as a “pleasant occupation for invalids” by Armstrong’s in Lyttleton, who also took the opportunity to advertise their wide range of household linens, pyjamas, and dressing gowns suitable for those convalescing (or perhaps just lounging) at home:

|

| Advertisement for Armstrongs Ltd., Lyttleton Times, 28 November 1918, Page 7. |

One advertisement suggested that “to fill in the time pleasantly and profitably we recommend everyone to lay in a stock of Magazines, Books and Papers, which can be procured at lowest prices at Alf Robinson's, Booksellers”, while another promoted a gramophone as a sure way to keep your family at home rather than risking the dangers of going out: “’The boys stay home at nights now!’ Every mother might say that – if suitable home enjoyment was provided – entertainment that would counter the attraction of outside amusement.”

Perhaps the wisest advice – equally applicable to our own time as when it was written a hundred years ago – came from Dr Joseph Frazer-Hurst, medical superintendent of Whangarei Hospital. His recommendation was to “let all the light and air you can into your houses and do not let your mind become depressed,” and suggested that the best thing to do for the time being was to simply “stay at home and grow vegetables.”

Author: Harriet Rogers, Heritage Collections

For more on the 1918 influenza pandemic, listen to our series of talks recorded at Tāmaki Pātaka Kōrero - Central City Library in October 2018.Influenza 100: Geoffrey Rice - Why do we still need to know? Part One

Influenza 100: Geoffrey Rice - Why do we still need to know? Part Two

Influenza 100: Sue Berman - The lived experience; remembering 1918-1920

Influenza 100: Jason Reeve - NZ Victims

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.