Tally Ho! Thrills and spills hunting in New Zealand

Among the traditions toffee-nosed English emigrants brought with them to New Zealand was the ancient upper-class custom of hunting with horses and hounds. The ‘sport’ of hunting was popular in most rural districts of the North and South Islands during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and, despite its opponents, continues among a dwindling circle of wealthy devotees even to this day.

Men, women and even children on horseback followed the scarlet-jacketed masters, huntsmen and whippers-in as they thundered over the countryside on the trail of their prey. In England, hunts actually had the wily fox to chase. However in New Zealand, their antipodean counterparts had to make do with terrorising the humble hare.

The first hares to reach New Zealand apparently jumped ship from the Eagle and swam ashore at Lyttelton, Canterbury in 1851. Between 1867 and 1872 the Canterbury and North Canterbury acclimatisation societies imported more English hares from Victoria in Australia. Acclimatisation societies were formed in many New Zealand regions during the 1860s to introduce familiar English animals and make the local countryside seem more like Home. But New Zealand’s warmer climate meant that many acclimatised animals bred prolifically and became pests. This was the case with hares. Eventually they spread into the North Island; probably after being introduced there too for hunting and sport but possibly also as stowaways on trading vessels.

Hares damage native vegetation and pasture and compete with stock animals for grass on pastoral farms. Apparently two or three hares can eat as much grass as a sheep. Hares can also damage vegetables and seedlings in nurseries, young trees and shelter belts. A pair of hares can destroy up to 100 trees in a single night.

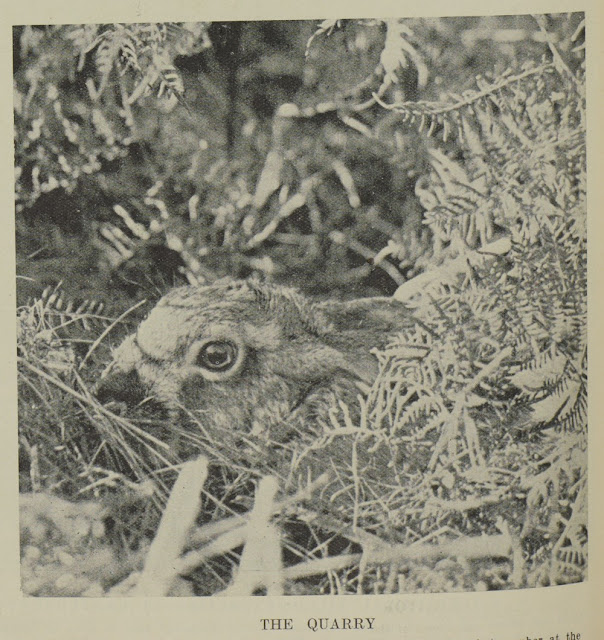

So hares became pests, which were hunted throughout New Zealand. At a Poverty Bay hunt in Whatatuta in May 1939 an Auckland Weekly News photographer covering the event unexpectedly came across the hunt’s quarry, which is pictured here:

Apparently, the animal was so ‘petrified by fear’ it allowed the photographer to stroke it before taking its picture. What happened next isn’t told, but hopefully the hunt had already galloped off into the distance and the hare lived to lead it a merry dance.

No doubt the hunting fraternity cherished nostalgic and romantic images of hunters, horses and hounds galloping across the field or ambling home after a hard day’s hunt:

To be a successful hunt rider, both rider and horse had to be confident and competent jumpers who could cope with solid walls as well as the usual antipodean post and wire fences. Here are some photos of some proficient jumpers:

But on occasion, accidents did happen. These riders were unexpectedly separated from their mounts:

Some riders who arguably should have known better seemed unable to take a hint about the unnecessary hazards attached to this dangerous pastime; although perhaps this is expecting a bit much of hare-brained, entitled aristocrats. The Prince of Wales fell off his horse at least twice while out hunting; and not long before this photo was taken had sustained a broken collarbone on the hunting field. Edward always thought he was rather good at chasing foxes. Even here he seems to be having a bumpy ride towards a precarious landing ...

Occasionally, hunting spills were serious accidents. In the following photo, an injured horsewoman is being carried away by ambulancemen after a fall during a hunt.

And hunting could sometimes be deadly. A well-known Auckland horsewoman, Mrs Wynn Brown, was killed when she fell from her horse, Hawker, during a Waikato Hunt meet at Cambridge. As with the terrified hare mentioned above, the Auckland Weekly News did not tell its readers what happened to Hawker. But one can imagine that hunts would be just as hard on failed horses as the other animals they abuse.

But for those who survived hunting’s perils, there was always the thrill (and kill) at the end of the pursuit. Sometimes a desperate hare would try to escape into a cave or underground hole. In this case, ‘sporting’ hunt followers would help the huntsman dig the hare out, before throwing the poor creature to the baying hounds who would tear it apart.

The following photo is of the Christchurch Hunt’s hound pack after they caught and killed the hare in an open field at Aylesbury in Canterbury.

When the hounds caught the hare above ground there was often time for the huntsman to wade in and beat the hounds off so that, in the words of Delabere P. Blaine’s Encyclopaedia of Rural Sports (1840) he could ‘save the remains of poor puss [so] that she may yet have the honour of gracing the table of the hunter.’ In the top photo in the following sequence the hounds have caught the hare in the ditch, while on the lower left the huntsman seems to be giving the hounds their reward after retrieving the hare’s carcass from their midst.

But some animals did get away. 1939 : a people's history : 'The war nobody wanted' (2019), Frederick Taylor recounts the following anecdote. Once the English Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain was pruning trees at his country house, Chequers. Suddenly a terrified stag burst onto the lawn, with the horns of the local stag hunt audible in the distance. Chamberlain instructed his chauffeur, James Joseph Read, to open the doors to the coal cellar, and the stag obligingly rushed in. Chamberlain told Read to close the doors, just before the hunt arrived. As instructed, Read denied all knowledge of the animal’s whereabouts. After the hunters rode off Chamberlain told Read to release the stag which raced off, hopefully to enjoy peace in its time.

Men, women and even children on horseback followed the scarlet-jacketed masters, huntsmen and whippers-in as they thundered over the countryside on the trail of their prey. In England, hunts actually had the wily fox to chase. However in New Zealand, their antipodean counterparts had to make do with terrorising the humble hare.

The first hares to reach New Zealand apparently jumped ship from the Eagle and swam ashore at Lyttelton, Canterbury in 1851. Between 1867 and 1872 the Canterbury and North Canterbury acclimatisation societies imported more English hares from Victoria in Australia. Acclimatisation societies were formed in many New Zealand regions during the 1860s to introduce familiar English animals and make the local countryside seem more like Home. But New Zealand’s warmer climate meant that many acclimatised animals bred prolifically and became pests. This was the case with hares. Eventually they spread into the North Island; probably after being introduced there too for hunting and sport but possibly also as stowaways on trading vessels.

Hares damage native vegetation and pasture and compete with stock animals for grass on pastoral farms. Apparently two or three hares can eat as much grass as a sheep. Hares can also damage vegetables and seedlings in nurseries, young trees and shelter belts. A pair of hares can destroy up to 100 trees in a single night.

So hares became pests, which were hunted throughout New Zealand. At a Poverty Bay hunt in Whatatuta in May 1939 an Auckland Weekly News photographer covering the event unexpectedly came across the hunt’s quarry, which is pictured here:

|

| Auckland Weekly News. The Quarry, 1939. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19390524-40-5. |

Apparently, the animal was so ‘petrified by fear’ it allowed the photographer to stroke it before taking its picture. What happened next isn’t told, but hopefully the hunt had already galloped off into the distance and the hare lived to lead it a merry dance.

No doubt the hunting fraternity cherished nostalgic and romantic images of hunters, horses and hounds galloping across the field or ambling home after a hard day’s hunt:

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Opening of the hunting season in Auckland, 1931. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19310506-44-2. |

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Riding to the hounds at a country meet, 1939. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19390607-51-1. |

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Over the hill to the hunt, 1939. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19390830-52-5. |

To be a successful hunt rider, both rider and horse had to be confident and competent jumpers who could cope with solid walls as well as the usual antipodean post and wire fences. Here are some photos of some proficient jumpers:

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Mr Buchanan taking a stonewall on Ben, 1907. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19070704-11-1. |

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Mr Rawson jumping a post and rail fence, 1902. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19020904-3-2. |

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Mr Herrold of Waiuku taking a wire fence, 1902. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19020904-3-3. |

But on occasion, accidents did happen. These riders were unexpectedly separated from their mounts:

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Ormonde blunders in the Palace hunting contest, 1926. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19260422-40-4. |

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Spectacular spill in Sydney,1932. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19320406-30-3. |

Some riders who arguably should have known better seemed unable to take a hint about the unnecessary hazards attached to this dangerous pastime; although perhaps this is expecting a bit much of hare-brained, entitled aristocrats. The Prince of Wales fell off his horse at least twice while out hunting; and not long before this photo was taken had sustained a broken collarbone on the hunting field. Edward always thought he was rather good at chasing foxes. Even here he seems to be having a bumpy ride towards a precarious landing ...

|

| Auckland Weekly News. The Prince of Wales goes hunting again, 1926. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19260422-54-2. |

Occasionally, hunting spills were serious accidents. In the following photo, an injured horsewoman is being carried away by ambulancemen after a fall during a hunt.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Lady rider injured on the hunting field, 1931. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19310923-46-3. |

And hunting could sometimes be deadly. A well-known Auckland horsewoman, Mrs Wynn Brown, was killed when she fell from her horse, Hawker, during a Waikato Hunt meet at Cambridge. As with the terrified hare mentioned above, the Auckland Weekly News did not tell its readers what happened to Hawker. But one can imagine that hunts would be just as hard on failed horses as the other animals they abuse.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Hunting fatality at Cambridge, 1923. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19230531-46-5. |

But for those who survived hunting’s perils, there was always the thrill (and kill) at the end of the pursuit. Sometimes a desperate hare would try to escape into a cave or underground hole. In this case, ‘sporting’ hunt followers would help the huntsman dig the hare out, before throwing the poor creature to the baying hounds who would tear it apart.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. Unearthing a hare from a cave on Mr Massey’s property, West Tamaki, 1902. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19020904-3-4. |

The following photo is of the Christchurch Hunt’s hound pack after they caught and killed the hare in an open field at Aylesbury in Canterbury.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. ‘In at the Kill.’ 1929. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19290501-39-1. |

When the hounds caught the hare above ground there was often time for the huntsman to wade in and beat the hounds off so that, in the words of Delabere P. Blaine’s Encyclopaedia of Rural Sports (1840) he could ‘save the remains of poor puss [so] that she may yet have the honour of gracing the table of the hunter.’ In the top photo in the following sequence the hounds have caught the hare in the ditch, while on the lower left the huntsman seems to be giving the hounds their reward after retrieving the hare’s carcass from their midst.

|

| Auckland Weekly News. The hunting season under way at Auckland, 1939. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, AWNS-19390517-50-3. |

But some animals did get away. 1939 : a people's history : 'The war nobody wanted' (2019), Frederick Taylor recounts the following anecdote. Once the English Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain was pruning trees at his country house, Chequers. Suddenly a terrified stag burst onto the lawn, with the horns of the local stag hunt audible in the distance. Chamberlain instructed his chauffeur, James Joseph Read, to open the doors to the coal cellar, and the stag obligingly rushed in. Chamberlain told Read to close the doors, just before the hunt arrived. As instructed, Read denied all knowledge of the animal’s whereabouts. After the hunters rode off Chamberlain told Read to release the stag which raced off, hopefully to enjoy peace in its time.

Comments

Post a Comment

Kia ora! Please leave your comment below.